Working together: building the right partnerships

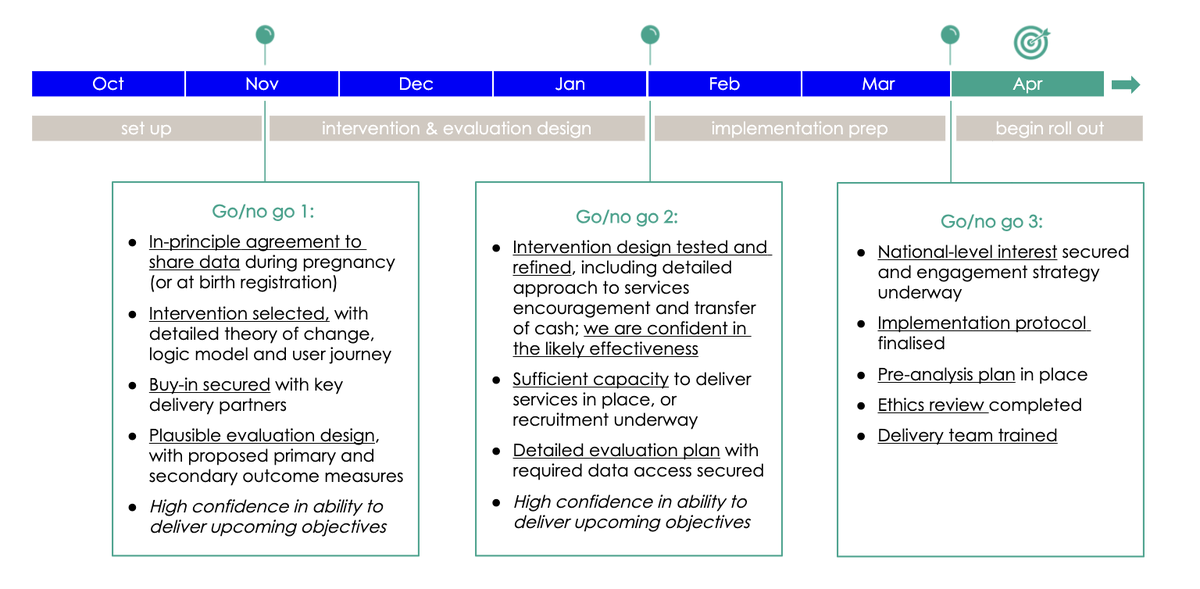

The grant only came to life through early, intentional collaboration. To guide progress and ensure we were ready at each stage, we developed a roadmap with a series of stages with clear “go/no-go” milestones (see the roadmap/stages).

This helped us set objectives at each phase (for example, data sharing) and avoid rushing ahead before key conditions were in place. You may want to adapt a similar tool to maintain momentum and accountability.

We recommend:

Secure senior champions early

Identify a committed leader at both the political and officer level to sponsor the work. Their support is critical to open doors, maintain alignment across departments and signal legitimacy to the wider network of key stakeholders and organisations.

Involve delivery teams from the start

This project was a collaboration across multiple teams. Working with welfare and benefits, Family Hubs, public health, and maternity services brought essential insights and helped shape a realistic, system-aligned pilot. Collaboration is vital to identifying what data sharing agreements will need to be in place (see Part 3).

Clarify roles and responsibilities

Who leads? Who holds the budget? Who delivers? Who can access data? Make this clear from the outset. To support these conversations, we created a simple template outlining the types of delivery costs you may want to consider. This can help clarify who is responsible for what, and how each part of the work might be resourced. (See budget planning worksheet).

Create a shared purpose

In Camden, we aligned with the Council’s We Make Camden missions and the Raise Camden taskforce alongside Nesta’s A fairer start mission. A shared goal helped unite diverse teams around a common cause.

Outcomes we hope to see

This pilot isn’t just about the cash grant. It’s about shifting how families experience and engage with local services. Our theory of change outlines how an unconditional grant, combined with proactive, supportive outreach, can help reduce financial stress, build trust, and encourage earlier and more confident engagement with support (see the theory of change). This is also illustrated in our post-intervention pen portrait, which brings the intended outcomes to life from a parent’s perspective (see the pen portrait – after the intervention). The goal is not only to meet immediate needs but to foster longer-term openness to services that support parental wellbeing and child development.

Our logic model maps out this pathway – from direct inputs such as the grant and Family Navigator offer, to short-term changes in service uptake, and longer-term shifts in attitudes, behaviour and outcomes. These expected changes guide our evaluation and may help shape your own local monitoring plans. (See the logic model)

How we are evaluating

To understand what difference this pilot makes – and whether it’s worth scaling – we’re running a randomised controlled trial (RCT) alongside a broader evaluation.

All eligible families receive the £500 cash grant, along with clear information in writing about support available through the Family Hubs. The RCT tests whether adding proactive, supportive outreach from a Family Navigator leads to greater engagement with Family Hub services in the baby’s first year of life, compared with the grant alone. This helps us understand whether a warm, human offer is essential or if clear, well-designed signposting is enough.

Beyond analysing engagement with Family Hub services, we’re also collecting data directly from participants. We’re surveying all participants a few weeks after they receive the grant and interviewing a smaller sample from both groups – before birth and after birth – to explore their experiences and how they’re using the support. Participation in the evaluation is opt-in and receiving the grant is not contingent on taking part. Families can access the support regardless of whether they respond to surveys or interviews.

In building our theory of change and evaluation plans, it was also important to be aware of the limitations of this pilot. For instance, the academic evidence tells us that cash transfers in pregnancy can improve infant health outcomes (see Part 1). Initially, we hoped we could use this programme to contribute to this evidence base. However, given the relatively small scale of the pilot programme, we determined through statistical power calculations that if the programme did improve infant health outcomes, we could not know that this was because of the pilot and not just due to chance. So we decided not to evaluate the programme’s impact on health outcomes, because if we found no impact, this may be misinterpreted as evidence that the programme ‘doesn’t work’. We instead decided to focus our evaluation on outcomes that come earlier in the causal pathway between the intervention and the ultimate health and wellbeing outcomes: engagement, service use, and parental stress and wellbeing.

The evaluation is being delivered in partnership with Nesta and UCL, with findings due in 2028.

Choosing