Part 3: Data flows

“I had no idea about it until I received a letter telling me about the children and families hub as well as the £500 grant and upon doing my own research, it was very clear.”

What is it?

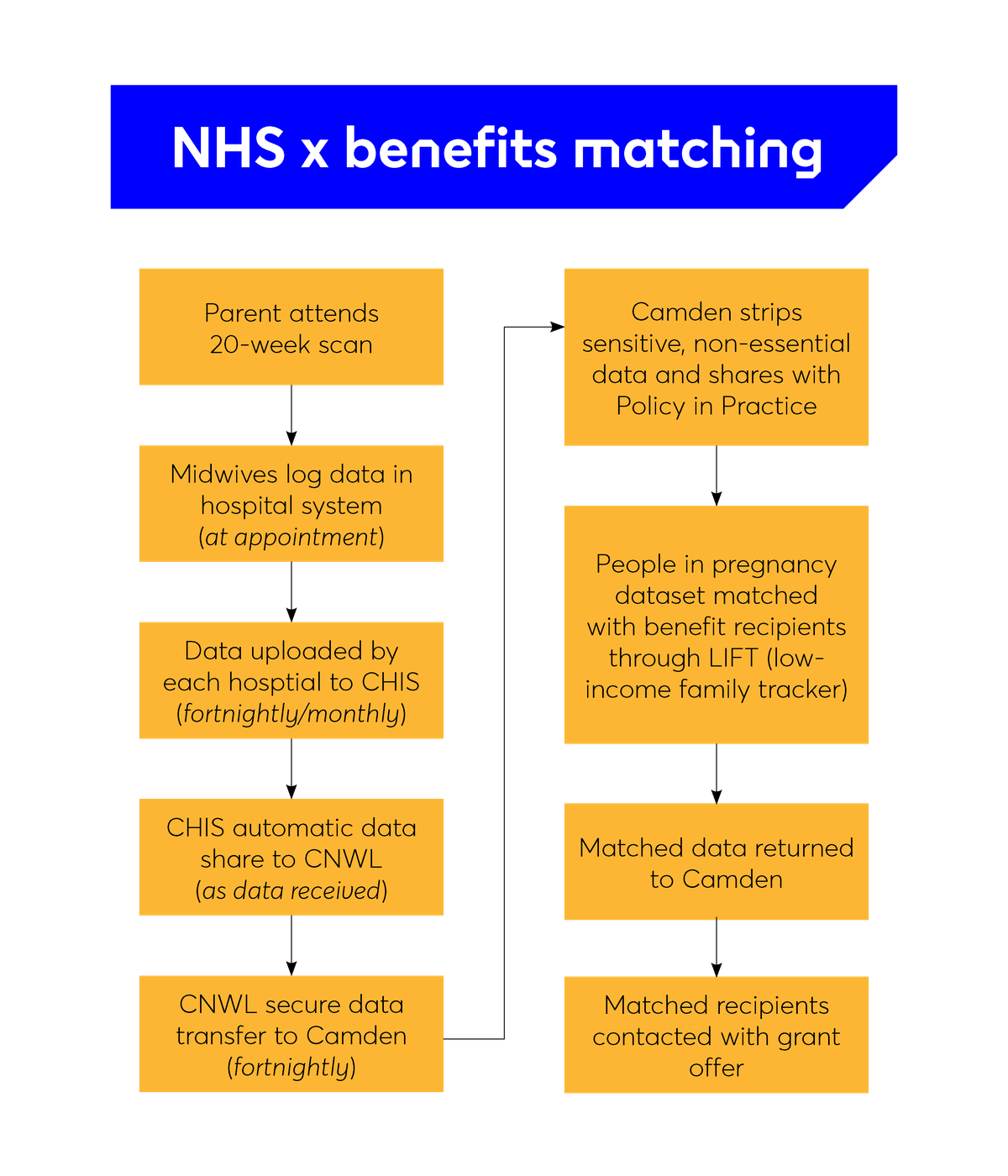

Our ability to provide proactive, targeted support in this pilot is underpinned by data flows. The data flows, data sharing governance and matching all take place behind the scenes from the perspective of the parents involved, meaning that they do not need to apply for the grant. For many, the first time they hear about the programme is when they receive the grant. To do this, we combine antenatal healthcare data (identifying pregnant people) with local benefits data (identifying low-income households). If an individual appears in both datasets, they will be offered the grant.

How to think about dataflows

Why it matters

Why are data flows important?

To follow one of our key design principles of reducing barriers to access, we knew it would be important to be able to reach out to people proactively, rather than rely on applications only. We know that it’s often the most disadvantaged groups who are least likely to reach out to or trust the council. If we wanted to be able to comprehensively deliver our intervention to all (or as close to all as possible) low-income families during pregnancy, we’d have to rely on our data to do this. While we recognise this data itself has gaps, and there would perhaps be those who wouldn’t be in receipt of benefits precisely due to this lack of trust, we still felt using this approach and creating an easy-to-access, non-coercive offer would be the best option to reach a higher number of people in a way that might lead to increased trust.

This meant we had to understand how data flowed through the different parts of the NHS, and where it was already being shared with the council, so we could expand on those existing processes and agreements. It was also important to know what data we would or wouldn’t be able to get (for example, would we get data very early in pregnancy from booking appointments, or later on from 20-week scans?). It was important to find this out early, so this could inform the design of the other elements of the programme, and so that we could ensure we weren’t creating something that would be impossible to deliver.

Why match data?

Matching NHS pregnancies data with benefit recipients data is the most comprehensive way Camden council has of identifying low-income families. Benefits are all means-tested, so by using the data we already own, we were able to avoid asking people to go through yet another process of application and means testing. However, we know this proxy of benefits data isn’t complete and that lots of people are underclaiming benefits they are entitled to. So, we also built in a process for self-referral (more details below).

Key consideration in Camden

Finding out what data exists and how to access it

Camden works in partnership with the NHS health visiting provider on its Integrated Early Years Service. We used this as a starting point to understand what data the NHS team we worked with had access to, and how we might extend this access to the team delivering the grant. We found that, by building on an existing data access agreement, we were able to get off the ground quickly with all our data centralised. In this case, it allowed us to access information from 20-week pregnancy scans across all hospitals that cover Camden through a single process. However, this data is coming from further downstream within the NHS itself, which means we are receiving it later in pregnancy (around 26-28 weeks) than if we’d approached each individual maternity ward and attempted to create new agreements with each (which would mean we’d get data at 22-24 weeks).

Navigating data protection and establishing the lawful basis for using data in this way

There are a number of principles under which the project team could establish an agreement to share data for the purposes of delivering an intervention such as this.

Camden already had an existing data agreement with the NHS for the purposes of delivering our health visiting service. We expanded this agreement under principles of substantial public interest but also of our duty under the Equality Act, of delivering services fairly and equitably across different demographic groups.

To expand on this agreement at Camden, we used the basis of Articles 6, 9 and 10 of the UK GDPR, and section 8 of the Data Protection Act 2018, which set out the acceptable conditions for processing and sharing personal and special category data for the purposes of an intervention like this. This work is also covered by our duty under the Localism Act 2011 (General Wellbeing), Care Act 2014, Children Act 2004, and Equality Act 2010. It was also under these principles that we were able to establish that our project would not need to operate under direct opt-in consent, but rather on an opt-out basis (meaning we would not need to wait for people to apply and directly consent to be contacted but we could contact them directly and let them tell us if they did not want us to reach out to them again instead).

As we were using benefits data as well, we also need to ensure compliance with the Department for Work and Pension’s Memorandum of Understanding, which governs the way local authorities use benefits data, and we framed this under the purposes set out in Annex C of this Memorandum, which detail how data might be used for local welfare provision.

Because we know that setting up data sharing and governance can take time, we started working on the data sharing agreement and the Data Protection Impact Assessment before we had a fully shaped intervention. As set out in the roadmap, we felt it was important to first establish that data sharing was possible in principle before dedicating months of work to designing a programme based on data sharing.

Identifying gaps in the data and how to account for them

We were aware in Camden that there would always be gaps in the data we hold. In our case, we identified two instances that were likely to represent our biggest gaps in data: people who were not being identified as pregnant in the NHS data (this could be for a number of reasons, including moving into the borough later in pregnancy, or receiving their maternity care at a hospital outside the borough); and people who were not in receipt of local benefits even though they would be eligible. We also knew there would be a percentage of Universal Credit recipients whose data we would not be able to access. There would also be some expectant parents under the age of 18 not entitled to benefits.

To mitigate against these risks, we also created a secondary route into our intervention, through a self-application form (see the application form for self-referrals). We circulated information through our Family Hubs, family workers, midwives and other community partners to pass on to families.

If someone believes they’ve been left out of our matching, they can apply through this form. When we receive an application, we assess each individually, as well as supporting relevant applicants with a benefit advice session to help them claim benefits they might be eligible for. This serves the dual purpose of supporting benefit uptake at the same time as accessing the pregnancy grant.