Greater than the sum of the parts

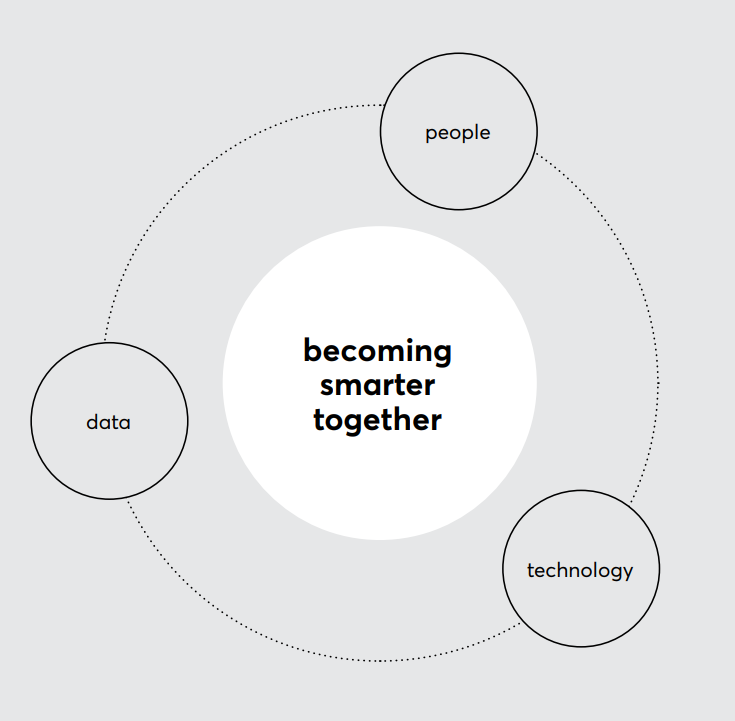

Collective intelligence is created when people work together, often with the help of technology, to mobilise a wider range of information, ideas and insights to address a social challenge.

As an idea, it isn’t new. It’s based on the theory that groups of diverse people are collectively smarter than any single individual on their own. The premise is that intelligence is distributed. Different people hold different pieces of information and different perspectives that, when combined, create a more complete picture of a problem and how to solve it.

Humans have of course been working together since the dawn of time. But since the start of the digital age, collective intelligence has really evolved. How is technology amplifying collective intelligence?

- Technologies such as the internet now help us to pool ideas in entirely new ways, and connect people across huge distances. Through this, we can bring more brains together - like Wikipedia does.

- Smart technologies help us generate new sources of data. We can use satellite imagery or mobile phone data, for example, to create new intelligence on our world and societies.

- Machine intelligence can enhance our human intelligence. Technologies like AI can analyse large volumes of data to help us make better predictions or more quickly understand lots of unstructured information.

The 19th century: The Oxford English Dictionary was produced through the collaboration of thousands of volunteers who submitted words and their etymologies to its editors.

The early 20th century: The statistician Francis Galton observed a competition to guess the weight of a cow at a country fair. He found that the individual answers varied widely, but when he added all the answers up and found the average, it was just 1lb different to the cow's real weight.

1920s: Gandhi used a challenge prize to reward designers - from anywhere - who could design a precisely specified cheap cloth loom.

1990s: Porto Alegre in Brazil pioneered a new approach to allocating public spending. The municipal government allowed citizens to debate and vote on how public funds should be spent in a process called participatory budgeting that has since been adopted all around the world.

Wikipedia: Thousands of individuals around the world contribute their knowledge and improve on each other's work.

Zooniverse: Over a million people are using the platform to analyse satellite images of space to help identify new stars.

Waze: Combines location data from mobile phones of commuters and crowdsourced information on accidents or hazards to create real-time traffic maps.

The big message is that we can now make the most of human intelligence at scale, novel data, and clever technology to help us solve complex problems.

Why do we need collective intelligence?

Have you ever wondered how we managed to put people on the moon, but can’t sort out how to care for our ageing population? Or how we can create machines that beat the world’s best chess players, but are struggling to stem the tide of online hate?

The difference is in the nature of those challenges. Humans (and machines) are very good at solving complicated technical challenges, where logical thought and linear thinking can get us to the finish line. But solving complex social, environmental, economic or political challenges is much harder. These challenges are often multidimensional and decentralised. They usually can’t be fixed with a silver bullet solution or by a single organisation. Often they emerge or change at a faster rate than our ability to act - especially when the environment is unpredictable.

The most critical challenges facing us today are complex challenges. The Sustainable Development Goals are an example of this type of challenge: interconnected, transboundary and requiring change at multiple levels from policies to institutions and individual behaviour.

Solving complex problems requires new approaches to problem solving: using new sources of data to rapidly understand the dynamics of what is happening; harnessing collective brainpower to generate multiple solutions much more quickly; facilitating space to think, reflect and decide collectively on a new course of action; and the capacity to harness data for real-time adjustments and orchestrating knowledge that enables others to act too.

To do this, organisations and communities need to become skilled in mobilising intelligence of all kinds - data, information, insights and ideas. In the 21st century, we believe this will matter as much as mobilising money or power. The collective intelligence design playbook is our first attempt to help organisations do this well.

Note: even if there are already well-proven solutions, or if one group of experts has all the relevant knowledge, there may still be value in using collective intelligence tools. For example, getting heart surgeons in the UK and parts of India to share their methods and regularly review data on survival rates sharply improved their performance, turning them from hundreds of individual experts into something more like a collective intelligence.

By bringing together diverse groups of people, data, and technology, we can create a collective intelligence that is greater than the individual parts in isolation. And by doing this, we can achieve things far beyond what any individual human or machine could achieve alone.

This playbook is designed to show you how to do this in practice.

How can collective intelligence help us?

Collective intelligence is a multiplier that brings new insights and ideas. When you incorporate collective intelligence into your way of working, it can help you to innovate and address problems more effectively.

Here is an overview of four ways that collective intelligence can help you:

1) Understand problems

Generate contextualised insights, facts and information on the dynamics of a situation.

It'll help you have a better understanding of problems through crowdsourcing, using novel data, or combining existing data sets to generate insights, facts, information or predictions. Examples of this are PetaBencana, a platform that crowdsources reports of flooding in Jakarta from citizens on Twitter to create real-time flood maps used by citizens; and Haze Gazer*, a crisis analysis and visualisation tool that provides real-time situational information by combining multiple data sets to enhance disaster management efforts.

*This project was active on intial publication of the playbook in 2019 but is now no longer active.

2) Seek solutions

Find novel approaches or tested solutions from elsewhere. Or incentivise innovators to create new ways of tackling the problem.

It'll help with finding solutions to a problem either through tapping into the collective brainpower of citizens, a wider pool of innovators, or seeking out tested solutions from elsewhere. Examples of this are Wefarm, a free SMS peer-to-peer information service for small-scale farmers in East Africa; or BlockByBlock, where citizens can co-create their community space. Tools like AllOurIdeas allow citizens to contribute their ideas about what their city should look like.

3) Decide and act

Make decisions with, or informed by, collaborative input from a wide range of people and/or relevant experts.

It'll help you to make more informed and inclusive decisions by bringing together a diverse range of people and relevant actors to discuss, prioritise and implement ideas. An example of this is vTaiwan, a hybrid online and offline consultation process to crowdsource citizen priorities and achieve consensus among competing perspectives. Tools like Loomio and Pol.is are enabling online group decision-making at scale on policies, budgets, planning and more.

4) Learn and adapt

Monitor the implementation of initiatives by involving citizens in generating data, and share knowledge to improve the ability of others.

It'll help you with learning and sharing what works through crowdsourcing information and creating shared repositories of knowledge. Examples include Public Lab’s* work to hold BP accountable for the Gulf oil spill clearup through citizen monitoring, and the creation of open source tools to help other community groups monitor environmental changes. The Human Diagnosis Project crowdsources and ranks diagnostic advice from thousands of doctors to provide ongoing training for health professionals and medical students.

*This project was active on intial publication of the playbook in 2019 but is now no longer active.

You can use collective intelligence at any stage in a typical innovation process, for policy design or designing new products and services in business.

What are the unique benefits of collective intelligence?

In addition to helping you understand problems, find solutions, make decisions and learn, there are some particular benefits of using collective intelligence as an approach. These include:

1) Improved ability to respond to issues in a more timely and effective way:

For many organisations, responding to complex problems is often made difficult by a lack of current or useful data, slow innovation pipelines and disagreement on how to proceed. Using collective intelligence to mobilise new sources of data (from sensors to citizen-generated information) and ideas will generate more comprehensive and up-todate insights, and more appropriate solutions for action. Collective intelligence can also help stakeholders, experts and affected communities come to greater agreement on priorities for action.

- Hayat (formerly AIME) can predict the location of the next outbreak of dengue fever up to three months in advance. It does this by combining data on confirmed cases of dengue from doctors, with multiple datasets on the factors that affect the spread of dengue.

- Resilience Dialogues was a set of facilitated discussions between experts and communities in the US. Combining their ideas led to more robust local climate action plans.

2) Increased power and ability of citizens to act:

Collective intelligence often involves people in generating information and opens up information for people to use. People’s ability to make decisions and power to act is increased when they have relevant and timely information about their situation and options. This enables citizens to share responsibility in tackling social problems.

- Madam Mayor, I have an idea is a participatory budgeting exercise that allows Paris residents to have a say in how the City’s local investment budget is spent. The government has allocated 500 million Euros over five years for projects to be decided in this way.

- Peta Bencana creates real-time flood maps from citizen reports on Twitter, enabling residents of Jakarta to make informed decisions about how to navigate around the city.

3) Smarter cities and communities:

When collective intelligence projects integrate different types of available information they can help to coordinate and influence the activities of people and organisations in new ways. By doing this, collective intelligence initiatives can act like a central nervous system for cities or local communities - helping them to react, remember, think and plan.

- The ET CityBrain system* deployed in a handful of cities in Asia integrates data from a network of sensors across the city to coordinate traffic and optimise public service delivery.

- Waze Connected Citizens project crowdsources input from people moving around a city and public data on top of Google Maps to improve the efficiency of day-to-day operations.

*This project was active on intial publication of the playbook in 2019 but is now no longer active.

What are the three forms of collective intelligence?

Collective intelligence projects can take many different shapes, and they can use a wide range of different methods. Here is an overview of the three main forms of collective intelligence. Each brings people and/or data together in different ways.

Connecting data with data: This form of collective intelligence often brings together multiple and diverse datasets to help generate new and useful insights. Data collaboratives, data warehouses and open APIs are some of the methods that are typically used in these data-driven collective intelligence projects.

- VAMPIRE is an early-warning system for climate impacts. It combines multiple datasets on population and socioeconomic data from household food security surveys with data on rainfall anomalies and vegetation health. The system then maps economic vulnerability and exposure to drought to anticipate the areas where people might need need most help.

Connecting people with people: This form of collective intelligence is the oldest. It can facilitate distributed information production, problem-solving, co-creation and prediction-making. Methods can include crowd forecasting, deliberation and peer-to-peer exchange.

- DARPA’s red balloon challenge placed ten red weather balloons around the US and tasked entrants with finding them all. A team from MIT won the competition by leveraging online networks and offering monetary prizes incentives.

- Nesta’s 2019 crowd prediction challenge asks individuals to assign probability forecasts to major events related to Brexit. These forecasts are then aggregated to produce a ‘wisdom of the crowd’ score. The crowd correctly predicted that the UK’s exit from the EU would not happen as originally planned at the end of March 2019.

Connecting people with data: This form of collective intelligence brings both people and data together. It often involves crowds generating, categorising, cleaning, sorting or tagging unstructured data, photos or PDFs. Citizen science, crowdsourcing, and crowdmapping are typical methods to achieve this.

- Earth Challenge 2020 aims to engage millions of global citizens in collecting one billion data points on air and water quality, pollution and human health. Citizen science volunteers around the world, working with professional scientists, will collect and share data of their local communities on an unprecedented scale, providing new insight on the state of our environment.

- The Missing Maps project engages thousands of volunteers tracing areas where official maps are limited or do not exist at all. This first phase of mapping is carried out by volunteers working remotely at home who trace satellite imagery into OpenStreetMap. Next, community volunteers add local detail such as neighborhoods, streetnames, and evacuation centres. Humanitarian organisations then use mapped information to plan risk reduction and disaster response activities that save lives.

What is not collective intelligence?

In some respects, all of human civilisation is an expression of collective intelligence. But there are lots of examples of practices that are the opposite of what we see as good collective intelligence. Such as:

- Closed organisations that make no use of the ideas and experience beyond their boundaries.

- Dictators and autocrats making decisions alone, or just relying on their intuition.

- Crowds that lack any common language or frames and so become a cacophony of voices and views without any mutual listening (like much contemporary social media).

- Crowds joined together by belief, ideology and dogma, and resistant to new information or ideas.

- Markets shaped by incentives that encourage myopia in relation to risks.

- Using collective intelligence methods to surveil participants or manipulate behaviour and outcomes.

- Extracting data from a crowd without offering any reciprocal benefits to contributors or failing to act on the insights generated.

These examples demonstrate that collective intelligence is far from the default in society. It is only through careful and deliberate design choices that we can get closer to making the most of the different resources of intelligence available.