Now you’re ready to start designing your collective intelligence project, here’s how to get going.

With your group, identify which collective intelligence purpose will help you tackle your challenge.

- Find the correct navigation page in the Collective Intelligence Design Playbook: activities PDF (activities PDF).

- Understand problems starting from page 8.

- Seek solutions starting from page 12.

- Decide and act starting from page 16.

- Learn and adapt starting from page 20.

- Print out the collective intelligence design canvas template, on page 7 of the activities PDF, (A3 or A2) and the specific design questions relevant to your selected purpose.

- Use the navigation page to see which activities are suggested, and pick those that you think will be most useful for your group and project. You should use them to explore the design questions in greater depth.

- Print out any prompt cards or worksheets you need.

- Work through the design questions set out at each stage with your group. Identify someone to be the group facilitator.

- Populate your canvas as your group answers the design questions. Allow time for reflection and iteration.

- Use activities such as prototyping to bring your project to life and identify any aspects that are missing or need to be changed.

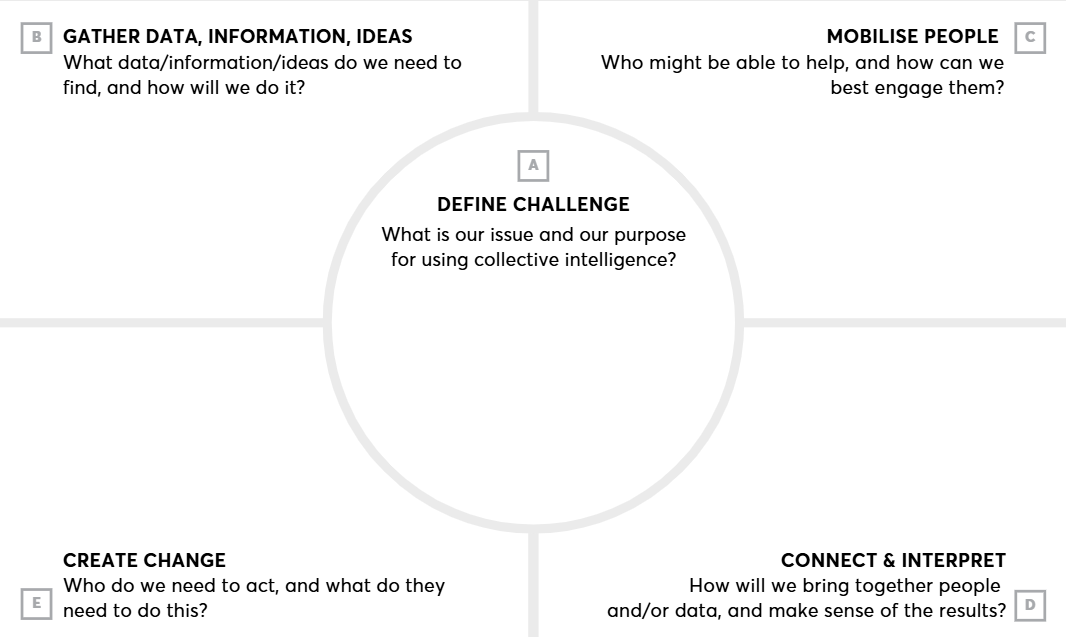

Template of a collective intelligence project design canvas.

Purpose: Understand problems

Purpose: Use collective intelligence to understand problems by generating contextualised insights, facts and information on the dynamics of a situation.

Common characteristics:

- Connects multiple types of data (for example, satellite data with crowdsourced mapping of a location).

- Uses novel data sources or proxy data (for example, light source data to measure GDP).

- Often involves crowdsourcing data (for example, experiences or information) from people.

- May use machine intelligence to analyse combined datasets or create models.

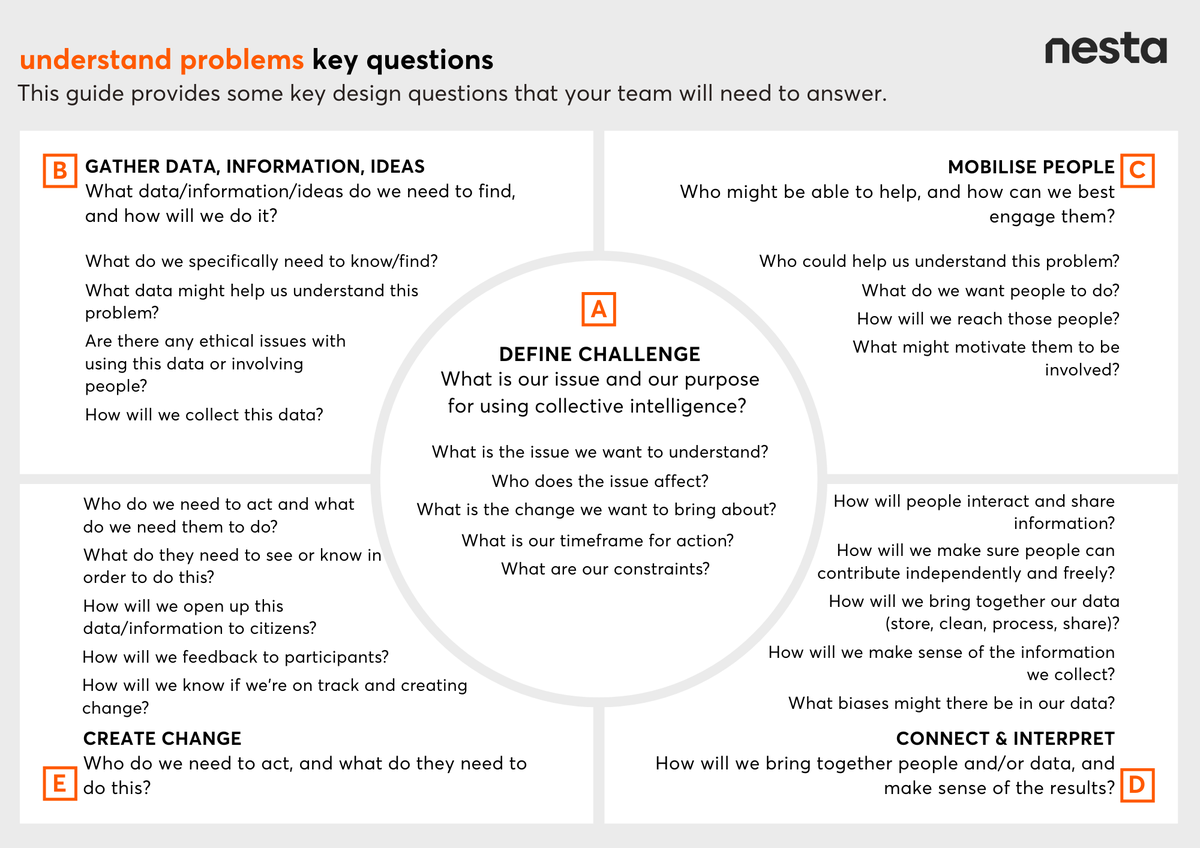

Design questions: Answer these design questions to complete the collective intelligence design canvas to understand problems.

Activities: Mix and match activities that will help you to answer the design questions if you’re stuck or if you want to explore in more depth. The table, on page 10 in the activities PDF, shows which are relevant if you are designing for understand problems.

This is a collective intelligence project design canvas filled in with key questions under each design stage for the purpose of understanding problems.

Purpose: Seek solutions

Purpose: Use collective intelligence to seek solutions by finding novel approaches or tested solutions from elsewhere. Or incentivise innovators to create new ways of tackling the problem.

Common characteristics:

- Searches academic/scientific literature for proven approaches.

- Connects with other organisations/individuals who might already be working on this issue.

- Invites a wide range of potential innovators to find a new/better solution.

- Sometimes using machine learning tools (including text analysis) to sift data more quickly and/or rank results.

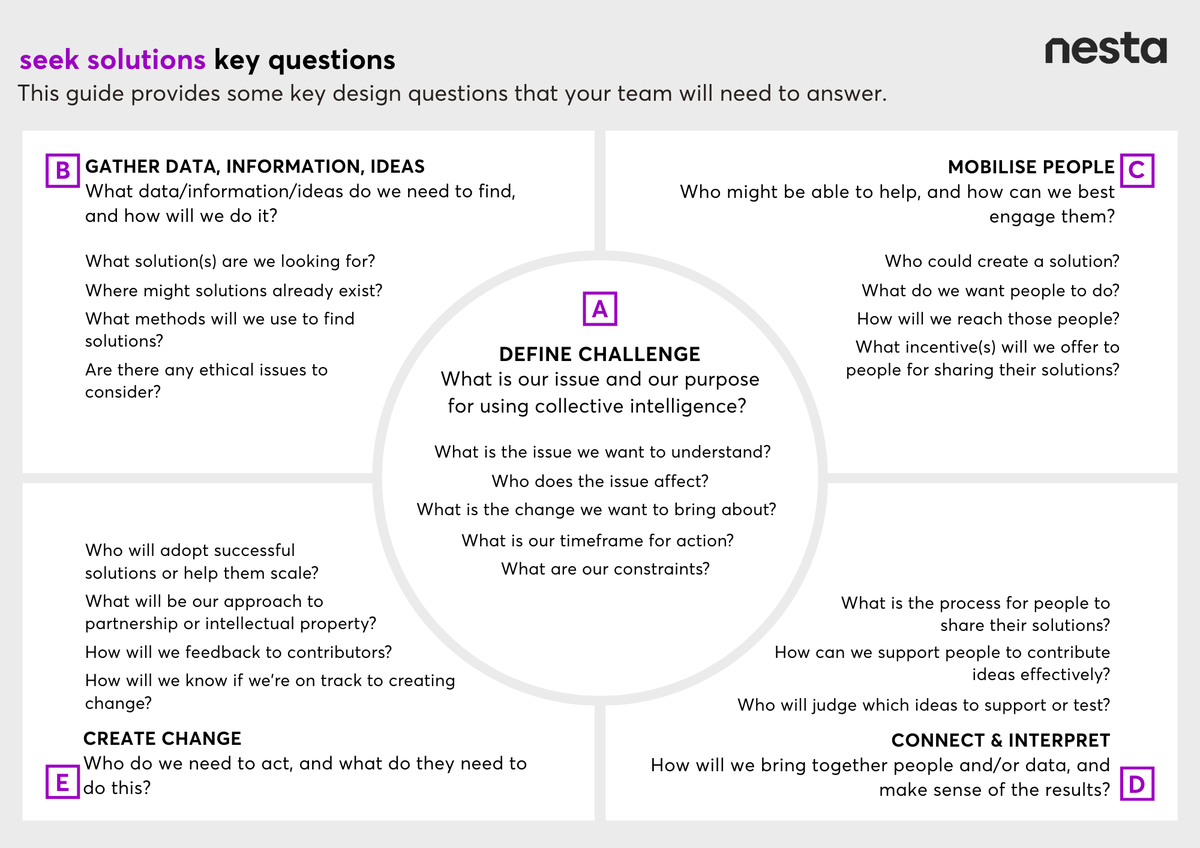

Design questions: Answer these design questions to complete the collective intelligence design canvas to seek solutions.

Activities: Mix and match activities that will help you to answer the design questions if you’re stuck or if you want to explore in more depth. The table, on page 14 in the activities PDF, shows which are relevant if you are designing for seek solutions.

This is a collective intelligence project design canvas filled in with key questions under each design stage for the purpose of seeking solutions.

Purpose: Decide and act

Purpose: Use collective intelligence to decide and act by making decisions with, or informed by, collaborative input from a wide range of people and/or relevant experts.

Common characteristics:

- Brings together a diverse range of stakeholders who are affected and/or knowledgeable about an issue.

- Often involves online or in-person group deliberation on an issue.

- May include voting and ranking of peer ideas or organisational policies.

- May be combined with collaborative group exploration to understand the problem and seek solutions.

- Sometimes uses machine learning tools such as natural language processing to cluster or summarise information.

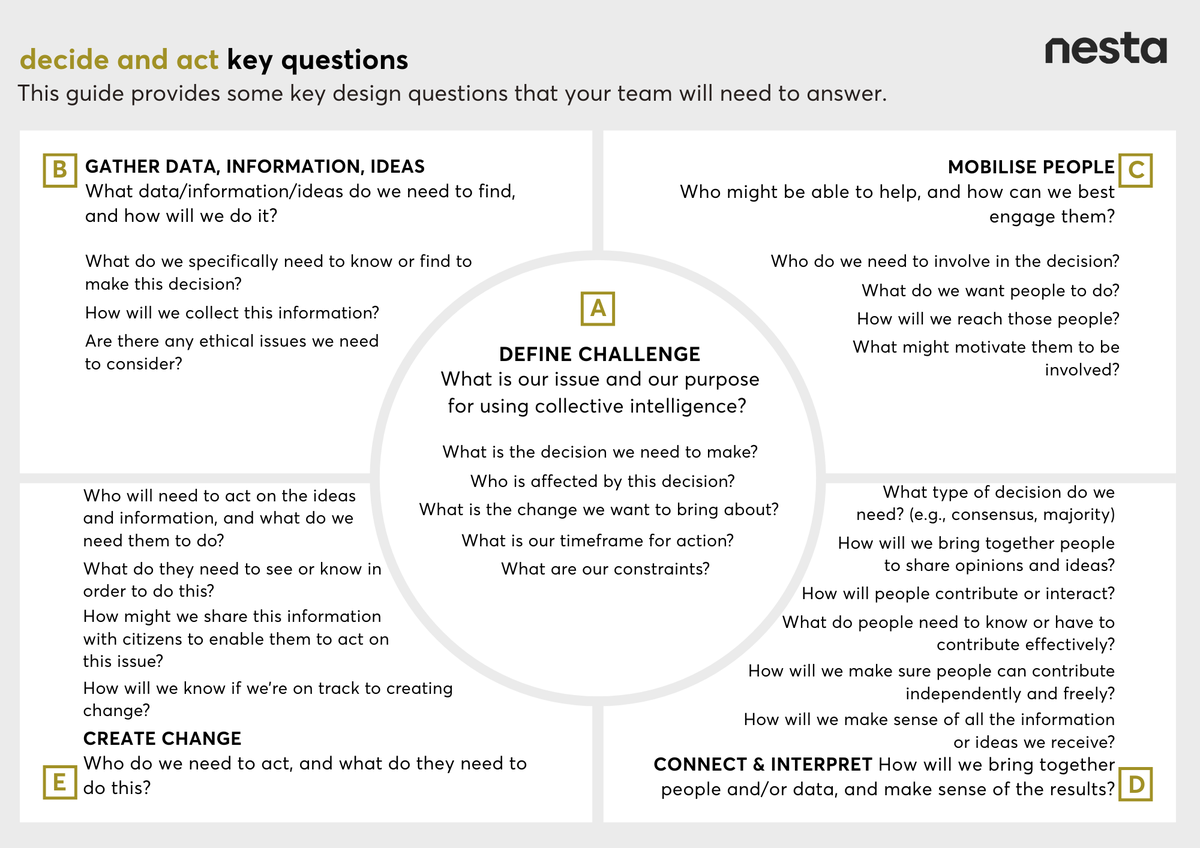

Design questions: Answer these design questions to complete the collective intelligence design canvas to decide and act.

Activities: Mix and match activities that will help you to answer the design questions if you’re stuck or if you want to explore in more depth. The table, on page 18 in the activities PDF, shows which are relevant if you are designing for decide and act.

This is a collective intelligence project design canvas filled in with key questions under each design stage for the purpose of deciding and acting.

Purpose: Learn and adapt

Purpose: Use collective intelligence to learn and adapt by gathering data to monitor the implementation of initiatives, and share knowledge to improve the ability of others.

Common characteristics:

- Mobilises data generated by citizens - either actively through crowdsourcing or passively (for example through call detail records).

- Combines multiple sets and types of data.

- Creates open repositories of data and/or tools.

- May use machine learning algorithms to identify patterns in data and automate adjustments.

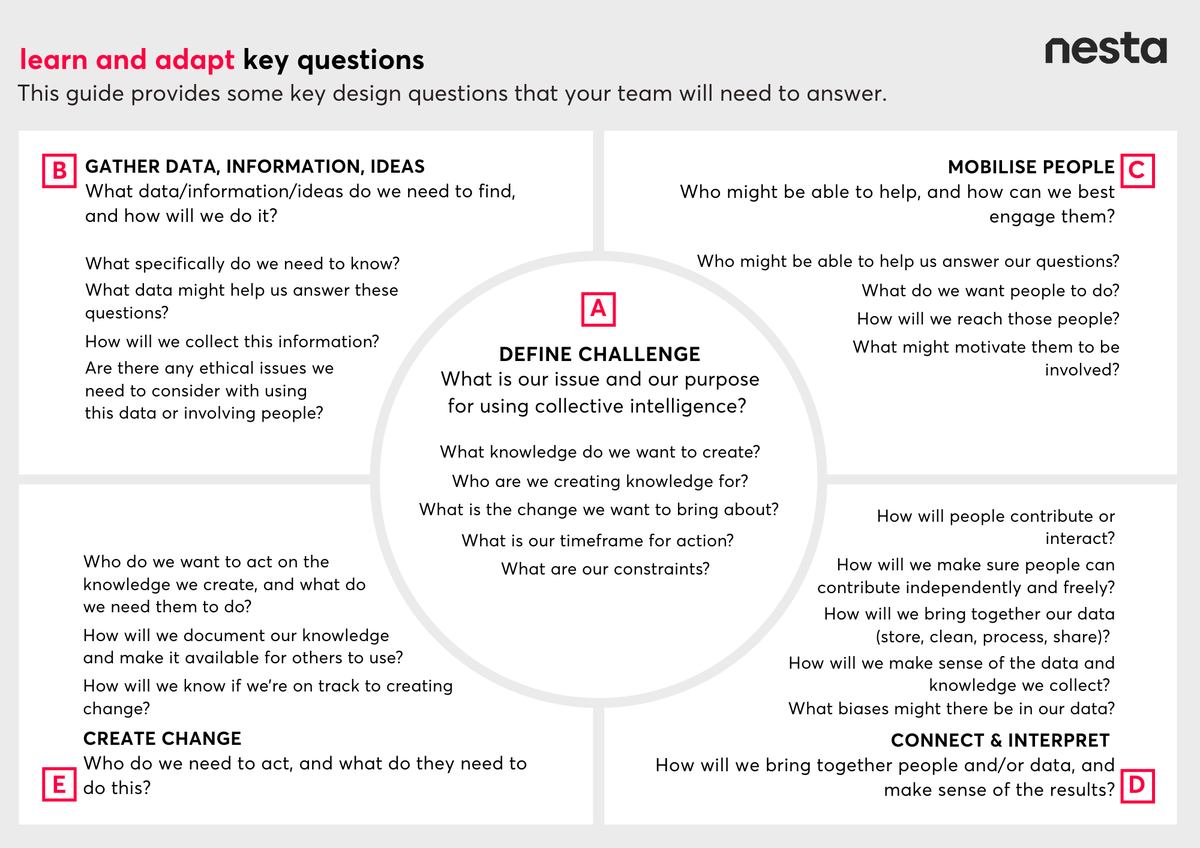

Design questions: Answer these design questions to complete the collective intelligence design canvas to learn and adapt

Activities: Mix and match activities that will help you to answer the design questions if you’re stuck or if you want to explore in more depth. The table, on page 22 in the activities PDF, shows which are relevant if you are designing for learn and adapt.

This is a collective intelligence project design canvas filled in with key questions under each design stage for the purpose of learning and adapting.

Once you’ve determined your purpose, go through each stage of the design process below.

Design stage: Define challenge

What is our issue and our purpose for using collective intelligence?

This stage will help you spell out your reason for using collective intelligence and help you to articulate the goal of your project. It is important because it will help you craft a guiding purpose for your project, which is necessary if you need to inspire others to join you. Collective intelligence involves many different approaches, methods and tools, and it can be easy to get caught up in simple technical fixes. Completing this stage will help you keep focused on the outcome.

Pointers for reflection and discussion:

- Try to do some desk-based research about your issue before commencing your collective intelligence project. It might be that the solutions you want, or the information you need has already been created by someone else.

- Consider what is the purpose of your collective intelligence project (to understand problems, seek solutions, decide and act, or to learn and adapt).

- Once you are clear about the problem that needs to be worked on, an important step is to describe, at least roughly, how it works as a system. What are the key factors that may be feeding into the problem? How much do we know about them? Who has the power to influence them?

- The issue map and the stakeholder map, on pages 29-32 in the activities PDF, can help a team and others to get a fuller sense of the issue. All of these can be thought of as hypotheses to be tested, partly through looking at the data and partly through talking to relevant people in the system. The mappings can be repeatedly returned to as a shared mental model of the problem, its causes and potential solutions. Don’t skip over this stage.

- Try to describe your challenge using the following formula:

Our problem is that… [insert a short description of your problem]. We want to... understand/find a solution to/decide/learn (delete as appropriate) [what?].

Design stage: Gather data, information and ideas

What data/information/ideas do we need to find, and how will we do it?

This stage will help you to define what data, information or ideas are needed for your collective intelligence project. It is important because collective intelligence projects almost always involve some form of data collection. There are now many more potential sources of data: from sensors and satellites; commercial data like mobile phone records which track travel patterns or economic activity; and citizen-generated data on everything from floods to corruption. Any project needs to start with a good understanding of the information it already has, what it can access, and what it needs.

Pointers for reflection and discussion:

- Sometimes data is proactively contributed by citizens, but it can also be collected passively via third parties or social media apps, with the consent of users.

- Consider what real-time ‘unstructured’ data such as posts on social media could reveal about the attitudes and values of a given subset of the population. Often less obvious data is more valuable than official data. For example in many countries mobile phone data is a better indicator of economic activity and its shifting location than anything else.

- Very local, tacit data that reflects lived experience or community knowledge can be complementary to formal data from sensors such as air pollution monitors or aerial satellite images.

- You should consider whether you need historical or real time data to help you address the challenge. Historical datasets might be readily available but when an issue is rapidly changing, they might not offer much insight into the current context.

- Some datasets are easier to collect than others, you should think about the timeline of data collection and whether you need one-off or regular contributions.

- It is important to consider how you will ensure your data is ‘fit for purpose’. This includes knowing the accuracy, interoperability with existing standards and quality requirements. Some common data quality protocols include validation by experts, peer review or requiring participants to undergo training.

- This also brings important questions around data ethics, data protection and responsible use of personal information. Clear rules around these need to be established before any data collection takes place.

Design stage: Mobilise people

Who do we need to involve, and how can we engage them?

Collective intelligence design can help you tap into distributed experience and expertise to answer your questions. For this to happen, the goal needs to be clear, 'the crowd' needs to be carefully defined and targeted, and the motivations and incentives of those participating need to be considered.

Pointers for reflection and discussion:

- Research shows crowd intelligence is enhanced by diversity. Whether you’re interested in engaging specific groups or sectors in society, or ‘the public’ more broadly, it’s important to consider how you will include people with diverse opinions and backgrounds, underrepresented groups and unusual suspects.

- Involving citizens or a wider group of stakeholders affected by the issue can help to legitimise the outcome of your collective intelligence project. It can also decrease the likelihood of disparate impact and seed behavioural change which might be fundamental to achieving the intended purpose.

- Some crowds are driven purely by curiosity or to make social connections. An individual’s motivations might also change over the course of a project, which impacts participation. Getting this right requires clarity on who your crowd is, and deciding a range of tactics to incentivise them (for example, monetary rewards or gamification). See the incentives and retention worksheet for more on this on pages 84-86 in the activities PDF.

- Sometimes crowds will be specific groups (for example, particular experts or affected populations), other times it will be open to anyone. Nonetheless it’s important to have a clear understanding of who your audience is, as this will have an important impact on the methods and tools you choose to engage them.

- It can be difficult to motivate and coordinate distributed crowds. Therefore the goals needs to be clear. Can you condense what you want the crowd to do into a series of simple tasks or statements? Use the engagement plan worksheet to decide how you’ll communicate with participants, on pages 80-81 in the activities PDF.

- It’s also important to consider the need to retain crowds over time. Some projects are designed with a lot of redundancy to ensure that high drop-out rates do not affect the success. Other types of collective intelligence rely on dedicated volunteers or participants over longer periods of time, meaning it’s crucial to build and maintain trust. This can take place through active facilitation, feedback and crowd facilitation on page 101-102 in the activities PDF (we return to some of these in following stages).

- Individual level feedback helps participants to develop their skills, which can in turn benefit the project as participants build expertise.

- Regardless of who is involved, what you’re asking people to do should be commensurate with their skills and experience. Try to acknowledge the value of different sources of expertise without prioritising one over the other.

Design stage: Connect and interpret

How can we connect people and data, and make sense of the results?

This stage will help you to understand how you can combine different sets of data to arrive at new insights, what role the crowd should play within this, and how to facilitate collaboration between a diverse group of people. Some projects use the power of the crowd to do the work of connecting or cleaning data. For others, the value is in how members of the crowd interact with one another by sharing opinions or ideas, or by upvoting and filtering different options. Data and crowdsourced information can be messy, or swathes of unstructured text. In order to make data useful and actionable, collective intelligence projects must find ways to easily interpret data. This can be for the benefit of the community or for the project leader to make sense of the results.

Pointers for reflection and discussion:

- There are a range of methods for connecting or bringing together different data or insights for collective intelligence projects. These can be categorised under three broad headings: ‘connecting data with data’ (for example, matching datasets, or establishing data collaboratives or warehouses); ‘connecting data with people’ (for example, crowds categorising, cleaning, sorting or tagging unstructured information, photos or PDFs) or connecting ‘people with people’ (for example, deliberation, peer-ranking or upvoting).

- Data-heavy projects will rely more on quantitative tools for exploring and analysing data. There are both open source and proprietary software packages to help with processing and visualising data. Other projects may need to involve much more active community participation, bringing people together in making sense of information.

- Interpreting data is sometimes non-contentious - it’s about understanding facts, or joining the dots to spot obvious correlations or trends (for example, rising infant mortality or the number of wildfires in a region). On other occasions the data will be much more subjective - it’ll require interpretation and evaluation by many different stakeholders, or perhaps even assessment by an independent group (as is the case for some challenge prizes).

- When interpreting data it’s always crucial to reflect on bias - especially when working with predictive models that are only ever as good as the dataset they are trained on. This also applies to offline groups, which can be susceptible to groupthink or confirmation bias. For some simple tactics see the overcoming biases guide on pages 99-100 in the activities PDF.

- For projects involving management of crowds, facilitation or moderation of both online and offline discussions can encourage more meaningful contributions. Providing feedback on what kinds of comments are most useful, and posing framing questions that redirect conversations or encourage elaboration help participants to focus on the topic at hand. The crowd facilitation guide on pages 101-102 and the ORID framework guide on pages 116-119 will help you to facilitate more productive online or offline conversations.

- A particular challenge when inviting ideas, suggestions or free-text contributions from large crowds is how to make sense of large volumes of unstructured text. One solution can be to use tools that constrain what people are able to do on the platform, so the results are easier to analyse and display (see the visualising citizen-generated data guide on pages 111-112 in the activities PDF). Artificial intelligence methods can also help to sort unstructured information into clusters to reveal underlying patterns.

Design stage: create change

How can we use and test our collective intelligence to create change?

The results of collective intelligence need to be made actionable and usable. In this stage you will prototype your project and develop a plan to test it. You will also consider how you're going to feedback to participants, to build trust and show people that their input had meaning.

Pointers for reflection and discussion:

- Know the minimum viable product needed. Raw data is of little use to most decision-makers, people delivering a service or to the community who you’re engaging. It’s unlikely that whoever is carrying out the action (for example, a frontline worker or service manager) will want a spreadsheet or raw data. Instead they will want the data conveyed in a way that is actionable and usable.

- Be aware of local resource limitations and access needs of your intended audience. It’s no use producing an online real-time map to visualise disaster-affected areas if most local residents don’t have access to computers or smart-phones. SMS, radio and peer-to-peer neighbourhood alert systems can be much more effective to ensure timely action in low-resource settings.

- Don’t forget to provide feedback to the contributors. Progress updates regarding the overall goal of the project reminds individuals that they are part of a collective, building a sense of contributing to a greater purpose.

- The broader impacts of collective intelligence can be auxiliary to the intended use. For example some of the most transformative results of citizen science projects can come from sustained behavioural change by communities stemming from their deep engagement with their local environment.