Distribution network operators (DNOs) are the private companies that own and run the local electricity networks delivering power to homes and businesses across Great Britain.

As the UK electrifies heat, transport and energy, these once largely invisible organisations are becoming central to reducing carbon emissions. This explainer sets out what DNOs do, why they matter, the challenges they face and how Nesta is working to remove barriers for households and shape strategic questions on the future of DNOs.

DNOs are regulated companies that own and operate the local electricity distribution network and keep voltage and capacity within safe limits. They are responsible for maintaining the cables, transformers and safety fuses that make up the local grid and provide power to homes and businesses in their area. They don’t generate electricity or sell it; they’re the behind-the-scenes infrastructure companies that keep the local grid working.

Note: it’s also worth distinguishing DNOs from electricity transmission operators. Transmission operators move electricity over long distances at very high voltages, from power stations to different parts of the country. DNOs then take that electricity and deliver it locally to homes and businesses using lower-voltage cables.

Most people never interact directly with their DNO, but you may have done so if you’ve ever:

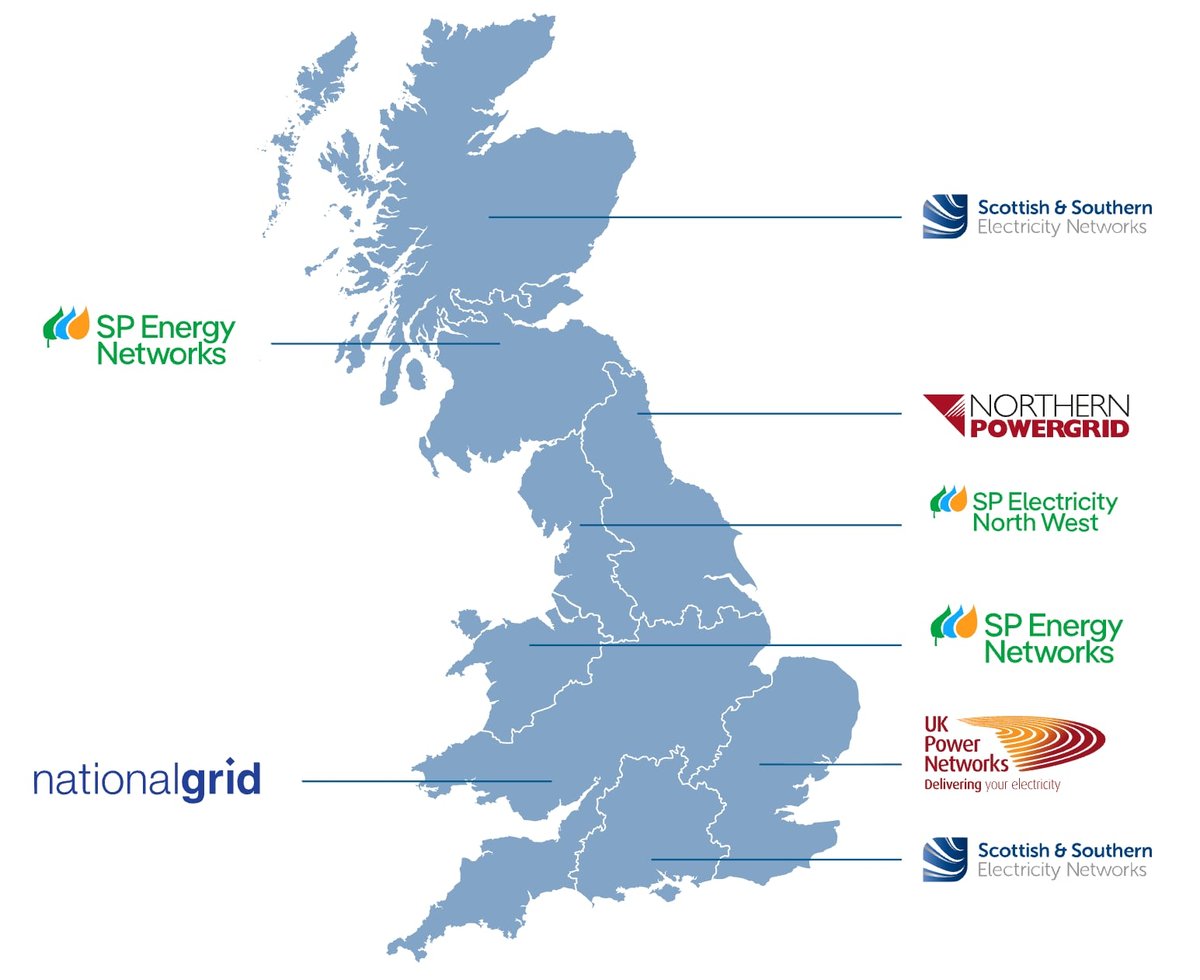

Six company groups hold licences for specific geographical areas (which are based on the former electricity board boundaries).

A map of Great Britain showing electricity distribution operators by region

Because customers cannot switch their local network provider, DNOs operate as regional monopolies and are tightly regulated by the energy regulator Ofgem.

Ofgem sets a price control system called RIIO (revenue = incentives + innovation + outputs). This framework sets how much revenue DNOs can earn over a five-year period, encouraging them to invest in network improvements, innovation and efficiency while ensuring they maintain high standards of service and security. DNOs are able to recover their costs through consumer bills. Approximately 20-25% of your electricity bill goes to your local DNO.

The transition to clean heat, electric vehicles and renewable generation is transforming the way people use energy. That means far more demand and complexity on local electricity networks than they were originally built for, especially at peak times. Modelling from the UK's independent Climate Change Committee (CCC) indicates that UK electricity demand could double or even treble by 2050 compared to today's levels. DNOs will need to plan for this increased demand and coordinate upgrades alongside changes to local demand.

If the network is unable to handle the additional load from homes and businesses connecting new low-carbon technologies, this could create connection delays and hold up progress.

Ofgem expects DNOs to avoid gold-plating the network by spending money without a clear demand for upgrades, but under-investing leads to bottlenecks and higher long-term costs. Striking the right balance is difficult under current rules.

DNOs need to predict where new demand will appear and match this with the infrastructure and capacity requirements. But the future uptake of EVs, heat pumps and new housing is uncertain, and DNOs aren’t fully plugged into local plans and strategies. At the same time, some DNOs lack the detailed data they need on their own assets to help them plan effectively.

Much of the national debate about grid connections has focused on delays to connecting new generation assets, such as wind farms and solar projects. Ofgem recently set out some proposals to help speed these up. But there is also a growing and related challenge around connecting new sources of electricity demand - from large developments of new housing to individual homes installing heat pumps, electric vehicle chargers and rooftop solar.

Households should notify their DNO (usually via their installer) and wait for approval before installing new EV chargers, heat pumps or solar panels. This is so they can check if the local grid can support the new electrical load, and what reinforcements may be needed. Analysis by Renbee finds that there are significant regional disparities in the time customers have to wait for approvals, with customers in some regions waiting an average of 58 days. Queues, unclear timelines and inconsistent requirements frustrate households and delay investment.

The energy transition is shifting the role of DNOs from more passive and responsive operators to more active and proactive. This is one of the biggest changes in the electricity sector in decades.

The key regulatory change that will govern this is the next price control period, RIIO-ED3. Ofgem has begun laying the groundwork and is consulting on the changes that will come in for April 2028. As part of this shift, DNOs are being asked to prepare long-term, integrated network development plans extending to 2050. This reflects an increasing expectation that DNOs play a strategic role, not just in keeping the lights on, but in shaping the long-term path to significantly reducing carbon emissions - including heat decarbonisation, EV charging rollout, distributed generation and demand flexibility.

There is a growing interest from the UK government in exactly what this strategic role could look like.

This has raised live questions about whether DNOs could take on a more direct role in elements of household decarbonisation - for example through financing or coordinating local delivery of low-carbon technologies.

Nesta is working to understand how local electricity networks are shaping - and sometimes constraining - the UK’s transition to low-carbon heat.

From a household perspective, we are investigating the barriers that affect heat pump uptake. In some areas, DNO processes and network constraints can introduce delays and additional costs. We are analysing where these issues arise and what practical changes could make the system work better for households.

We are also looking at this from the installer’s point of view. Many installers face complex and time-consuming DNO application processes when connecting new heat pumps. Through Nesta’s agentic AI residency, in partnership with Renbee, we are exploring whether AI systems could manage parts of the DNO application process on behalf of installers - reducing admin burdens and speeding up connections.

Renbee is also working with DNOs directly to help shape their plans and readiness for RIIO-ED3 to ensure they actively work to address bottleneck issues ahead of 2028. If you want to support this journey or learn more, you can get in touch via their website.

Finally, we are examining the bigger strategic question of whether DNOs should play a greater role in heat decarbonisation overall - including how local network planning, investment and coordination could better support a rapid, fair transition to clean heat.