Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant Toolkit

The Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant began with a simple but powerful goal: to offer timely, meaningful support to pregnant people experiencing financial hardship – on their terms.

In 2025, Camden Council, in partnership with the NHS and Nesta, began piloting the Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant project. The pilot programme consists of two elements: a £500 cash grant given to pregnant people towards the end of their pregnancy, and proactive outreach from a Family Navigator – a specially trained council officer who can connect participants with other support available to them. The programme is targeted specifically towards low-income parents, and we use linked administrative data to identify eligible participants, without them needing to apply.

This toolkit sets out the details of Camden Council’s Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant service, including how it was designed, who it aims to serve, the change it hopes to achieve and how, and details of what is needed to deliver the service. This toolkit focuses on setting up the service and not on any ongoing work involved in delivery and monitoring.

How to use this toolkit

This toolkit is primarily for staff at local or combined authorities who may consider implementing a similar intervention. You may be interested in just the cash grant, just the Family Navigator intervention, or some other targeted outreach activities to pregnant people or new parents, made possible through data linkage. In the toolkit, we set out these elements – grant, Family Navigator, data – separately, explain the rationale behind them, and provide a checklist and resources to help you adapt and implement such a programme in your context.

The image at the foot of the page presents a visual overview of the toolkit. While we separately cover the pregnancy grant, the Family Navigator and the data flows within this toolkit, there is substantial overlap in the rationale and detail of implementation, as shown in the DIY checklist.

Please note that this toolkit is provided for information purposes only, and users rely on its content at their own discretion.

DIY checklist

DIY checklist

Use this checklist (with hyperlinks to relevant sections of the toolkit) as a guide during the planning and design stage of your own pilot.

Scoping and resourcing

☐ Define your purpose

What are you aiming to achieve - higher service engagement, increased uptake of unclaimed benefits, improved health outcomes, or all of the above? For whom? Collate a brief evidence base to clarify the issue and who it affects. Use local data and insights from families to build shared understanding across teams.

☐ Build your partnerships

Do you have buy-in from other stakeholders, such as early years, public health, welfare and benefits, NHS maternity services, and senior leadership? Who will lead on delivery?

☐ Secure funding

Are there budgets held by the council or with your local health partners which could be used for this purpose? Could you use some of your Household Support Fund (HSF) allocation in this way? From April 2026, the new Crisis and Resilience Fund (CRF) will replace HSF – can you design your three-year CRF programme to include a scheme like this?

Data and targeting

☐ Identify your cohort (see 'Key considerations in Camden')

Find out how many families you might support and set clear eligibility criteria. Can you securely access and link NHS maternity data with local benefits data to proactively identify eligible families? If not, how else might you be able to identify a similar cohort based on data you do have access to?

☐ Get data sharing in place

Data sharing and governance can take some time. Who owns the data you need? Are data sharing agreements already in place? Which lawful basis will you rely on for the use of the data? If required, begin drafting data sharing agreements and a Data Protection Impact Assessment as early as possible.

Design and testing

☐ Understanding existing provision (see 'Key considerations in Camden')

Find out what outreach is currently happening. What is the gap that needs to be filled and are others already working on this? Consider this within the council, health services and the voluntary and community sector.

☐ Decide on your offer

- What will you provide?

- How much money? (see 'Key considerations in Camden')

- Proactive outreach via a trusted frontline staff member?

- Signposting of services and supporting handover of cases to relevant professionals? (see 'Key considerations in Camden')

- A combination of the above? (see 'Why pair cash with services?')

- How will you provide it?

- Format – cash or bank transfer or both? (see 'Key considerations in Camden')

- Frequency – one-off grant or installments? (see 'Key considerations in Camden')

- Timing - when in pregnancy? Or will you deliver it post-birth? (see 'Key considerations in Camden' and the FAQ: 'What if I don’t have access to pregnancy data?')

☐ Plan for safeguarding and sensitive circumstances (see 'Plan when the grant will be delivered')

Have you identified how to respond if a parent discloses risk or needs additional support? What steps will you take if a family experiences pregnancy loss or distress during the project?

Consider implementing:

- training for Family Navigators or staff on how to respond with care

- clear safeguarding protocols and referral pathways

- sensitive messaging that acknowledges pregnancy loss in a compassionate, non-stigmatising way.

☐ Develop and test your delivery assets with your target audience

Start preparing templates and tools such as:

☐ Plan for monitoring and evaluation (see 'do I need to evaluate?')

Do you want to do an impact evaluation? If so, what outcomes will you track? Will you need ethics approval? Can you partner with a university or external evaluator?

Designing for impact

Designing for impact

A simple idea, centred on families.

The Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant aims to provide proactive, holistic and personalised support to pregnant people experiencing financial hardship. To achieve this, we had to put trust in parents, remove barriers to access and design services that feel welcoming, sensitive, and non-stigmatising.

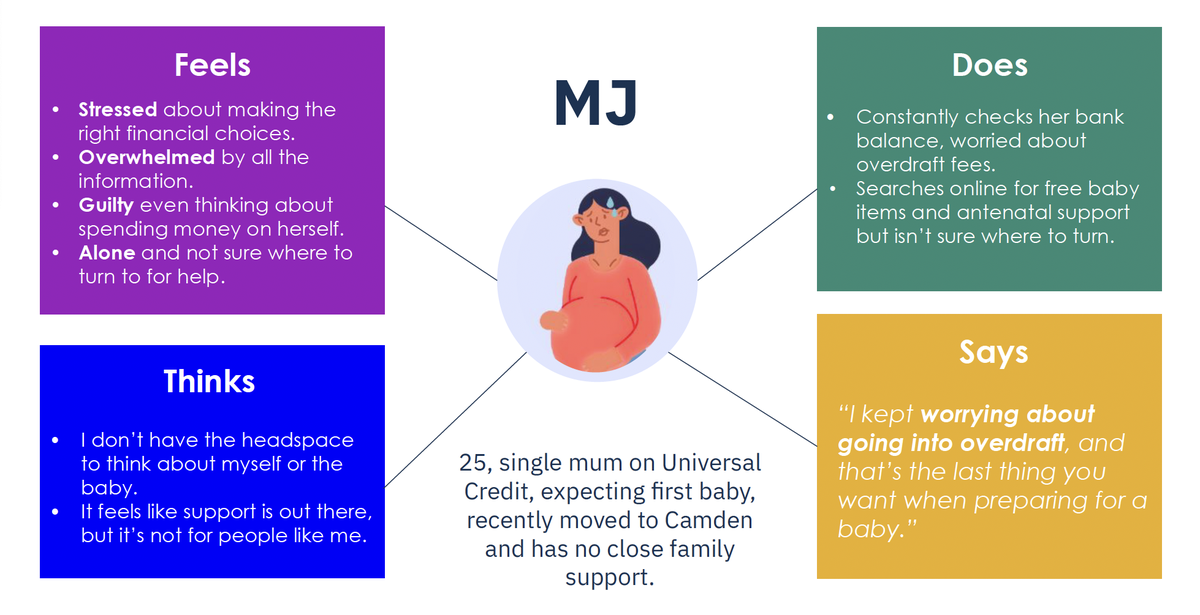

From the outset, we grounded our design in the lived experience of families, drawing on insights from user research with parents in Camden. We used a composite persona – MJ, a 25-year-old first-time mum on Universal Credit who feels overwhelmed by her situation – to represent the perspectives of those who often feel excluded from traditional services (see the pen portrait).

Her experience informed the end-to-end user journey by helping us challenge assumptions, reduce friction and build trust from the first interaction (see the user journey).

Importantly, this also meant designing a programme involving multiple teams in the council, to ensure that what we offer parents is centred around their needs, not around institutional structure and budgets. We know that financial support in pregnancy can improve maternal and infant health (see Part 1). But we also know that there are many other types of support that councils can offer, and different families have different needs. We wanted to design a programme that brings together all that the council can offer to help parents prepare for their baby’s arrival.

Turning that idea into action required thoughtful design, strong cross-sector collaboration and a shared commitment from senior leaders to doing things differently. This section outlines Camden’s approach, the principles behind it and what we hope to achieve, along with tools to help you design a version that works in your own local context.

Our design principles

We built this pilot around three core principles.

1. Lead with cash-first support

We believe families know best what they need. Unconditional cash empowers people and gives them the flexibility to meet their needs in the way that works best for them, whether that’s paying off debts, buying essentials, doing something that supports their wellbeing, or in another way entirely. There are no strings attached and no requirement to report how the money is spent.

This approach is grounded in a strong evidence base. Research shows that financial support during pregnancy can reduce maternal stress and improve outcomes for babies, especially in low-income households. See Part 1 for a summary of this research.

2. Minimise barriers to access

We aimed to reach families who might benefit most, including those not already engaging with services. By linking existing NHS and benefits data (see Part 3), we could proactively identify eligible families, reduce drop-off in engagement and avoid the stigma of needing to apply for means-tested support.

To keep it accessible and non-intrusive, parents do not need to apply. Instead, pregnant people are contacted proactively and can receive the grant as cash or by bank transfer. This flexibility acknowledges varying comfort levels with technology and reinforces our commitment to meeting families where they are.

3. Build trust through a relational approach

Our user research revealed that many families may not engage with Children’s Centres and Family Hubs (referred to collectively as Family Hubs throughout this toolkit) due to feeling overwhelmed, uncertain about where to go for support during pregnancy, or a perception that the services are not designed for them. To address this, we paired the cash with a warm introduction to local services.

To do this, we introduced a novel Family Navigators service (see Part 2). Family Navigators are named, trusted people who reach out with a friendly phone call or a low-pressure meet-up at the local Family Hub. The aim isn’t to push services, but to build trust and give families the confidence to explore support on their own terms.

Things to consider

Working together: building the right partnerships

Working together: building the right partnerships

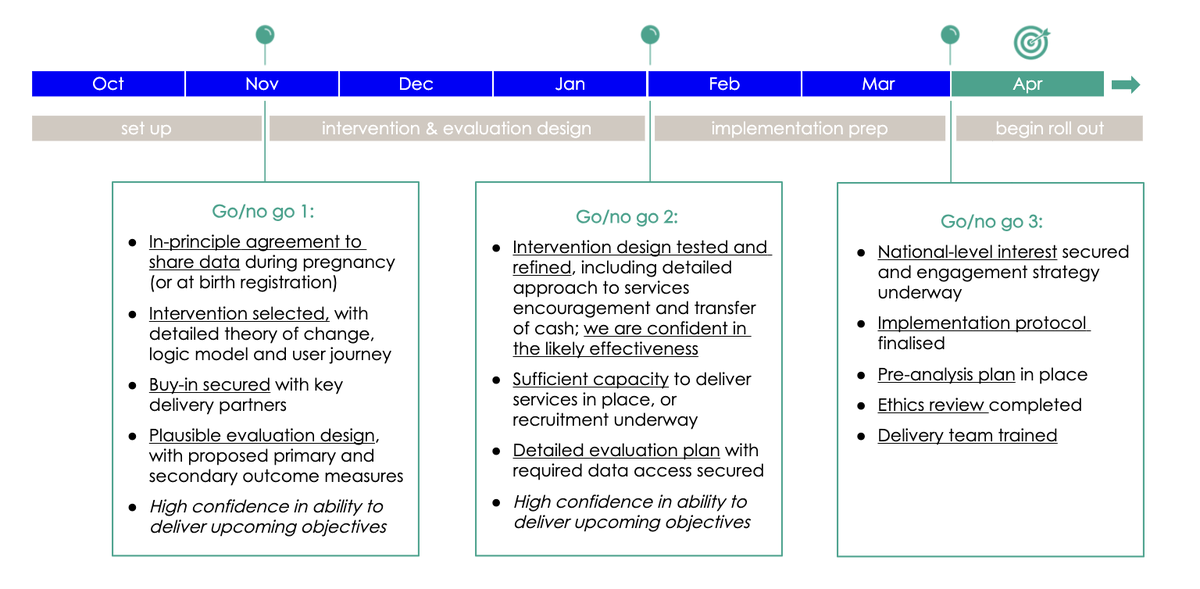

The grant only came to life through early, intentional collaboration. To guide progress and ensure we were ready at each stage, we developed a roadmap with a series of stages with clear “go/no-go” milestones (see the roadmap/stages).

This helped us set objectives at each phase (for example, data sharing) and avoid rushing ahead before key conditions were in place. You may want to adapt a similar tool to maintain momentum and accountability.

We recommend:

Secure senior champions early

Identify a committed leader at both the political and officer level to sponsor the work. Their support is critical to open doors, maintain alignment across departments and signal legitimacy to the wider network of key stakeholders and organisations.

Involve delivery teams from the start

This project was a collaboration across multiple teams. Working with welfare and benefits, Family Hubs, public health, and maternity services brought essential insights and helped shape a realistic, system-aligned pilot. Collaboration is vital to identifying what data sharing agreements will need to be in place (see Part 3).

Clarify roles and responsibilities

Who leads? Who holds the budget? Who delivers? Who can access data? Make this clear from the outset. To support these conversations, we created a simple template outlining the types of delivery costs you may want to consider. This can help clarify who is responsible for what, and how each part of the work might be resourced. (See budget planning worksheet).

Create a shared purpose

In Camden, we aligned with the Council’s We Make Camden missions and the Raise Camden taskforce alongside Nesta’s A fairer start mission. A shared goal helped unite diverse teams around a common cause.

Outcomes we hope to see

This pilot isn’t just about the cash grant. It’s about shifting how families experience and engage with local services. Our theory of change outlines how an unconditional grant, combined with proactive, supportive outreach, can help reduce financial stress, build trust, and encourage earlier and more confident engagement with support (see the theory of change). This is also illustrated in our post-intervention pen portrait, which brings the intended outcomes to life from a parent’s perspective (see the pen portrait – after the intervention). The goal is not only to meet immediate needs but to foster longer-term openness to services that support parental wellbeing and child development.

Our logic model maps out this pathway – from direct inputs such as the grant and Family Navigator offer, to short-term changes in service uptake, and longer-term shifts in attitudes, behaviour and outcomes. These expected changes guide our evaluation and may help shape your own local monitoring plans. (See the logic model)

How we are evaluating

To understand what difference this pilot makes – and whether it’s worth scaling – we’re running a randomised controlled trial (RCT) alongside a broader evaluation.

All eligible families receive the £500 cash grant, along with clear information in writing about support available through the Family Hubs. The RCT tests whether adding proactive, supportive outreach from a Family Navigator leads to greater engagement with Family Hub services in the baby’s first year of life, compared with the grant alone. This helps us understand whether a warm, human offer is essential or if clear, well-designed signposting is enough.

Beyond analysing engagement with Family Hub services, we’re also collecting data directly from participants. We’re surveying all participants a few weeks after they receive the grant and interviewing a smaller sample from both groups – before birth and after birth – to explore their experiences and how they’re using the support. Participation in the evaluation is opt-in and receiving the grant is not contingent on taking part. Families can access the support regardless of whether they respond to surveys or interviews.

In building our theory of change and evaluation plans, it was also important to be aware of the limitations of this pilot. For instance, the academic evidence tells us that cash transfers in pregnancy can improve infant health outcomes (see Part 1). Initially, we hoped we could use this programme to contribute to this evidence base. However, given the relatively small scale of the pilot programme, we determined through statistical power calculations that if the programme did improve infant health outcomes, we could not know that this was because of the pilot and not just due to chance. So we decided not to evaluate the programme’s impact on health outcomes, because if we found no impact, this may be misinterpreted as evidence that the programme ‘doesn’t work’. We instead decided to focus our evaluation on outcomes that come earlier in the causal pathway between the intervention and the ultimate health and wellbeing outcomes: engagement, service use, and parental stress and wellbeing.

The evaluation is being delivered in partnership with Nesta and UCL, with findings due in 2028.

Choosing

Part 1: The pregnancy grant

Part 1: The pregnancy grant

“I really appreciate the grant received, as that has helped my partner and I hugely, particularly in this day of age of the rise in cost of living in Camden.”

What it is

The Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant is a means-tested, unconditional £500 cash grant offered proactively to low-income pregnant people in Camden. It’s designed to be simple, supportive and non-stigmatising.

Crucially, most eligible families do not need to apply. Instead, the council uses existing data to identify eligible parents and reaches out directly to let them know they can receive the grant – either cash from an ATM or as a direct bank transfer (see Part 3 for more information on the data flows that facilitate this).

This approach aims to reduce financial stress during pregnancy, increase trust in public services and create a warm entry point to Family Hub support.

Why it matters

Why give cash during pregnancy?

We know from academic research that financial support during pregnancy can help prevent adverse outcomes for babies, especially in low-income households. Maternal stress is strongly associated with low birth weight, preterm births and long-term developmental risks. Providing unconditional financial support can help reduce that stress and improve outcomes for the child.

This is backed by the Family Stress Model, which outlines how economic hardship affects child development through increased parental stress. Evidence from the UK's previous Health in Pregnancy Grant (2009-2011) showed that a relatively modest £190 payment led to measurable improvements in birth weight and reductions in preterm birth, especially for younger mothers and those in more deprived areas.

Why pair cash with services?

Recent research suggests we may see greater impact when financial support is stacked with other offers, such as parenting advice or community connection. We do not yet have a lot of evidence on this, but there are ongoing projects in Scotland, England, Sweden and Australia testing the impacts of bundled support. In our pilot, we sought to test a different bundle, taking a cash-first approach to help recipients free up mental bandwidth and build trust - making it more likely that parents take up other helpful services, such as Family Hubs or Healthy Start vouchers. In our theory of change (see the theory of change), we set out why we think the impact can be greater than the sum of its parts. Our evaluation, when complete, will generate more evidence on this.

Key considerations in Camden

Here we outline some of the practical steps we took and decisions we made in Camden.

Find out how many families we might support

We estimated that there would be 800 low-income families receiving benefits and having a baby within a one-year period. To estimate this, we used:

- ONS data, which suggests that there are around 2,000 babies born annually to Camden residents. This is different from the number of births registered in the borough - many babies are born in hospitals based in Camden but live elsewhere, and birth registration is based on place of birth.

- Camden’s State of the Borough report says that approximately 40% of children in Camden live in low-income households - 40% of 2,000 would be 800.

- As an additional check, we know from the Department for Work and Pensions’ data that approximately 3,300 children aged 0-4 live in households receiving Universal Credit, which would imply 650 children aged 0. But we know not all low-income households receive Universal Credit.

This rough estimate helped with early financial planning so we could very quickly get a ballpark figure for how much the grant would cost.

Decide how much money to offer

We offered £500, informed by:

- past grant values (for example, the Health in Pregnancy Grant was £190 in 2009, so approximately £300 in 2025 prices)

- £500 is the approximate value of Child Benefit for a first-born child (£26/week), if paid weekly from the date that the MatB1 form is issued (around week 20 of pregnancy)

- cost of living pressures in London

- available budget

Define eligibility

To be eligible, we decided people needed to be:

- living in Camden or in housing provided by Camden Council (including temporary accommodation or a refuge outside of the borough, and residents living in Camden while under the responsibility of other local authorities)

- under 20 weeks pregnant from 1 April 2025, and with their 20-week scan no later than 31 March 2026

- receiving or eligible for qualifying benefits (such as Universal Credit, Housing Benefit, or Council Tax Support).

These eligibility criteria work in the vast majority of cases, but we also had to consider and specify how we would approach ‘edge cases’, such as multiple births, miscarriages and households with no recourse to public funds.

We used receipt of benefits as a proxy for low-income that we could easily identify using data we already had. But we know that not everybody on a low income claims benefits. We also know that not all pregnant people living in Camden would be having their baby with a hospital in our local NHS trust and that anyone who fell into our ‘edge cases’ would not come up through the main data match. We have therefore set up an option for self-referral (see Part 3 for more details) for those who might be under-claiming benefits, or receiving care from a hospital in another area of London.

Plan when the grant will be delivered

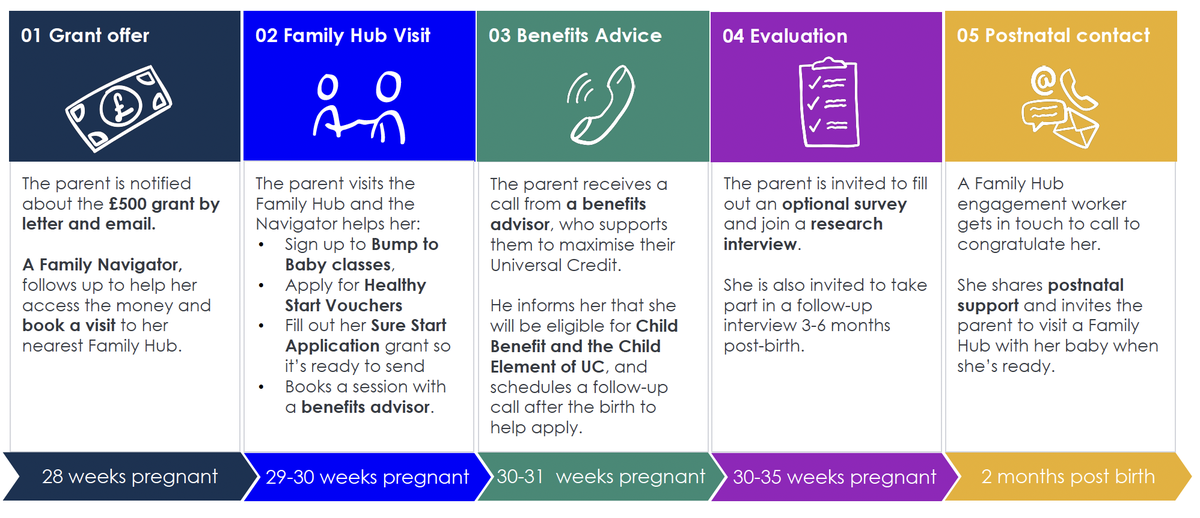

Participants are informed of their eligibility through a letter and email after their 20-week ultrasound.

This timing was chosen for practical reasons, as the data we receive from the NHS is from the 20-week ultrasound scan. We also considered the following.

- Parent preference: from user testing, parents told us that they prefer to be contacted after the 20-week scan, because this is when the baby becomes ‘more real’ and parents are more willing to engage in preparing for the baby.

- Possible pregnancy loss or termination: the NHS estimates that one in eight known pregnancies end in miscarriage. Up to one in four conceptions are aborted. We wanted to avoid contacting families who had experienced a pregnancy loss, because we were concerned this would be upsetting. We were unable to establish a process to ensure that data collected earlier in the pregnancy would be reliably updated with information on pregnancy loss, and therefore we favoured using data from the 20-week scan. This also aligns with when pregnancy data would be shared with the health visiting team, which allowed us to tap into existing data sharing (see Part 3), but also meant we would not be holding information on pregnant people before this was shared with local health professionals.

Decide on a one-off grant or installments

Participants are given a one-off £500 grant. We also considered splitting this amount into a series of installments to be paid throughout the pregnancy. However, when we asked parents about this in our user testing, most said they would prefer a one-off payment. A one-off payment was also administratively simpler for the council and participants.

Informing parents about the grant and delivering it

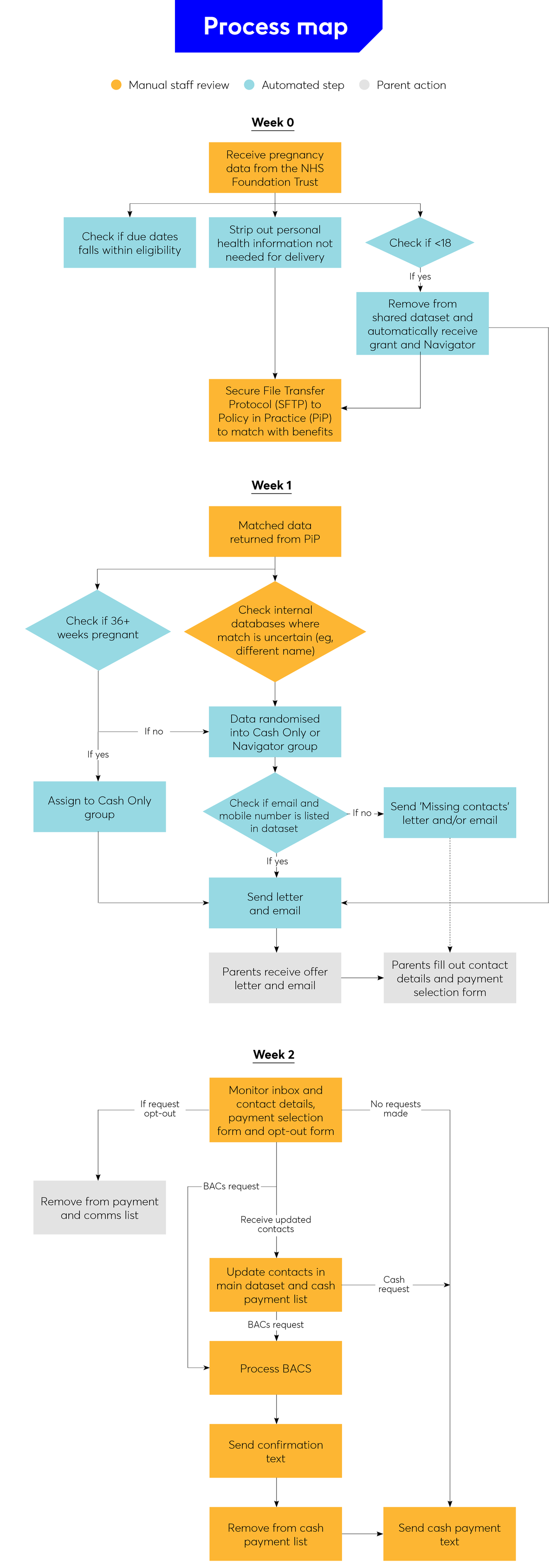

Recipients first receive an email explaining the grant and letting them know they will soon get a text message with instructions for withdrawing the cash from an ATM. A few days later, they then receive a letter with NHS, Family Hubs and Camden Council branding to reinforce legitimacy and trust. Alongside this, all recipients are offered the option to complete a form, which serves two purposes: to update any incorrect or missing contact details (such as email address or mobile number) and to indicate whether they would prefer to receive their grant by bank transfer instead of cash (see the process map).

Recipients then follow one of three routes:

- If we have their mobile number and they do not complete the form:

They automatically receive a text message within five days. This includes a secure code and instructions for withdrawing the money from an ATM. - If they complete the form and request a bank transfer:

The payment is made directly into their account within two weeks. - If we are missing contact details (email or mobile):

The recipient must complete the form first to provide their details and indicate their preferred payment method before the grant can be issued.

To support accessibility, all letters were translated into the seven most commonly spoken languages in the borough, with translations also available online.

The decision to pair an email with a letter was based on user testing. Because this grant is unexpected by most recipients, we wanted to ensure that communications felt official and trustworthy, and focus group participants told us they would trust a letter most, especially if it had the Family Hubs and NHS logos. We also know that many people’s contact details are out of date, hence the importance of contacting people through multiple channels.

Getting the word out

Beyond direct communications with parents, we also focused on briefing other professionals that families were likely to get in touch with to enquire about or validate the offer. This briefing helped to ensure professionals who work with parents knew about the programme, as well as helping recipients to verify the grant’s legitimacy through a council website or a trusted professional. We ran short briefings and provided a one-page practical information sheet, and an FAQ sheet for:

- midwives

- Family Hubs staff

- councillors

- other frontline staff undertaking outreach work with families (such as the Children and Young People health improvement team)

- local schools

- voluntary and community sector organisations we routinely work with.

We also set up a dedicated webpage, email address and phone line so people could research the grant and reach out to us independently.

What to measure

Part 2: Family Navigator

Part 2: Family Navigator

“I want to say a massive thank you for helping me [...] your kindness, empathy, and the warm way you approached everything really made a difference to me [...] I’ll definitely be making the most of the information and courses you shared with me, and if I need any more support, I won’t hesitate to reach out.”

What is it?

The Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant Navigator (Family Navigator) is an outreach worker based within Camden Council. The Family Navigator proactively contacts parents eligible for the Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant, ensures they have received the grant and offers information and support to access a range of other services. This includes welfare advice, birth and parenting preparation, and access to practical baby essentials such as clothing and beds. The conversation guide that Family Navigators follow when contacting parents is available in the Navigator conversation guide.

Rationale

Why provide a proactive outreach with information on available services?

While Camden’s Family Hubs are widely accessed by over 80% of local families, we know that the least accessed services on offer are antenatal programmes. When we speak to parents, we commonly hear how they wish they’d known about what was available earlier, or during previous pregnancies. We also know that at least 15% of families living in the most deprived neighbourhoods aren’t engaging with Family Hubs at all. We wanted to find ways to reach them better.

There are many support services available, but it can be difficult for parents to navigate the information and understand what is right for them. Providing personalised, one-on-one support makes this more manageable.

The Family Navigator also provides a warm introduction to broader council services. A key service Family Navigators can signpost families to is welfare advice. People do not always access all the benefits they are entitled to, and so accessing welfare advice services could further boost the financial resources available to families. This may be particularly useful during pregnancy and for families with young children, as benefit eligibility changes with the birth of a child.

Why a phone call and a visit?

Just as we know from our research that it’s important to offer the cash grant through different means of communication, we knew that it would be important for Family Navigators to have multiple ways of engaging parents. A quick initial phone call carries the same ease of access, optional uptake and friendly, supportive tone that the grant was designed to have. Being able to offer a follow-up visit to the Family Hub provides support for people to overcome any feelings of being intimidated or nervous about engaging with a new place and new people.

Tailoring the visits to parents’ needs and schedules also helps them feel that this is a personal and dedicated support offer for them, and it allows them to better express what they are interested in or feel they would appreciate support with. Multiple one-to-one interactions with the same Family Navigator allows a relationship to be built, which in turn creates the right opportunities for families to share if they are feeling stressed or low about any aspect of their pregnancies, and the Family Navigators are then well placed to help them manage the wide landscape of different support on offer.

Key considerations in Camden

Understand what outreach and engagement services already exist

The goal of Family Navigators is to present a cohesive offer to parents engaging with services, so as a minimum, it is vital to know what other outreach offers families may be receiving. There were no proactive outreach offers to the pilot’s specific population of pregnant people in receipt of benefits. However, the Family Hubs already have Information and Engagement Workers (IEWs), who provide an important service to families once their baby is born. The Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant team worked with the IEW team to ensure continuity of the two offers and that the extensive expertise of the IEWs was the basis for the new Family Navigators.

Defining our eligibility criteria

The Family Navigator offer had the same eligibility criteria as the Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant (see Part 1). However, it was agreed that the Family Navigator offer would be randomised to half the eligible population. This decision was taken due to resource constraints that made it unlikely that all eligible families could be contacted anyway, so there was an opportunity to randomise this resource allocation to facilitate evaluation.

If you are in a similar situation, consider reviewing Nesta’s guidance on running randomised controlled trials in early-years settings.

Plan when the Family Navigator will contact families

In our pilot, Family Navigators are contacting families within a few days of their grants being offered and scheduling Family Hub visits for the following couple of weeks. This allows for a period of continued engagement where we can build on the initial excitement about the Family Hubs Pregnancy Grant to encourage further engagement. It also means Family Navigators can act as a point of contact to troubleshoot any issues with accessing the cash, saving on further administrative resources.

The timing of this offer also took into consideration the stages of pregnancy. With grants being offered a few weeks after the 20-week scan (roughly around 28-30 weeks), we wanted to make sure Family Navigators reached out to parents early enough that encouraging them to a Family Hub visit would not coincide with the very end of their pregnancy, where there was a chance they could be put off by the travelling required, and so they would be welcomed into a Family Hub with enough time to still make the most of the antenatal offers available.

We also knew that, even if parents engaged with Family Hubs in this period of focused activity, there was a chance this engagement would drop off towards the end of their pregnancy, particularly for those who were not interested in antenatal offers. To bridge this potential drop in engagement, we worked closely with the IEWs and created a personalised handover and transition for after their baby arrives. The Family Navigator uses the Family Hub visit as an opportunity to introduce parents to an IEW. The IEW then also becomes a trusted and recognised contact and reaches out to parents post-birth, re-inviting them to the Family Hubs and reminding them of the offers available to them now they have their babies.

Selecting a core offer

We spent a lot of time understanding the existing offers to families antenatally, analysing service capacity, purposes and the target users of different programmes.

Working closely with our colleagues delivering these offers, we condensed our priority offers to include one main service offer for each category of outcomes. For example, we selected one antenatal class, one mental wellbeing programme, one service for accessing baby essentials, etc. This meant that we could train Family Navigators quickly and make sure they, or the parents they interacted with, weren’t overwhelmed by the nuance of different offers. It’s important to do this narrowing down in close collaboration with early years teams, who hold the best knowledge of each programme and the different strengths and capacity of each.

We made sure that all the programmes included in our core offer would be available to all or most grant recipients, so further eligibility wasn’t an issue. By condensing our core offer to eight elements (see the outcomes one-pager), we could also evaluate the impact of the Family Navigator contacts by quickly capturing the engagement with each of the eight core elements we selected.

Develop the engagement offer

Once we understood who the offer was for and what we wanted to prioritise offering to them, we developed the implementation plan for the Family Navigators. This included recruiting the Family Navigators, who were appointed to this role alongside their existing work as financial support coordinators within the financial support service. We selected these staff, rather than early years professionals, partly due to capacity in the different teams. Additionally, we wanted our Family Navigators to be able to offer the targeted welfare advice and support that many parents needed, and this group of staff was already highly skilled in that area.

Ultimately, the role of a Family Navigator can be created from different settings, and there is not necessarily a need for a new and dedicated role to be created to deliver this kind of pilot. The essential skills for a Family Navigator are relational skills, safeguarding training and knowledge of the local offer. We worked closely with early years teams to train our Family Navigators in the nuances of our Family Hubs offers.

Training our Family Navigators to be able to have a level of fluency on both sides of the offer – antenatal and Family Hub services, and financial support – was the key element that made this a strong role. Our Family Navigators also bring personal strengths to the role, too – for instance, their experiences as parents themselves and as users of Family Hubs, as well as being fluent in other languages to support engagement with our diverse communities.

Alongside the core offer, we developed the script and call procedure, as well as the in-person meeting guide, for the Family Navigators to follow during their contacts, creating a clear checklist of the key parts of the offer they should mention and directing them to further resources if parents were interested in other things beyond this.

We created a data capture plan (see the data capture table for navigators) that outlined what information the Family Navigators needed to record about each of their contacts, and where and how to record this data. We also created a bank of template communications Family Navigators can use to follow up from appointments (see Navigator communications). These facilitated our process monitoring and contributed to our wider evaluation.

What to measure

Part 3: Data flows

Part 3: Data flows

“I had no idea about it until I received a letter telling me about the children and families hub as well as the £500 grant and upon doing my own research, it was very clear.”

What is it?

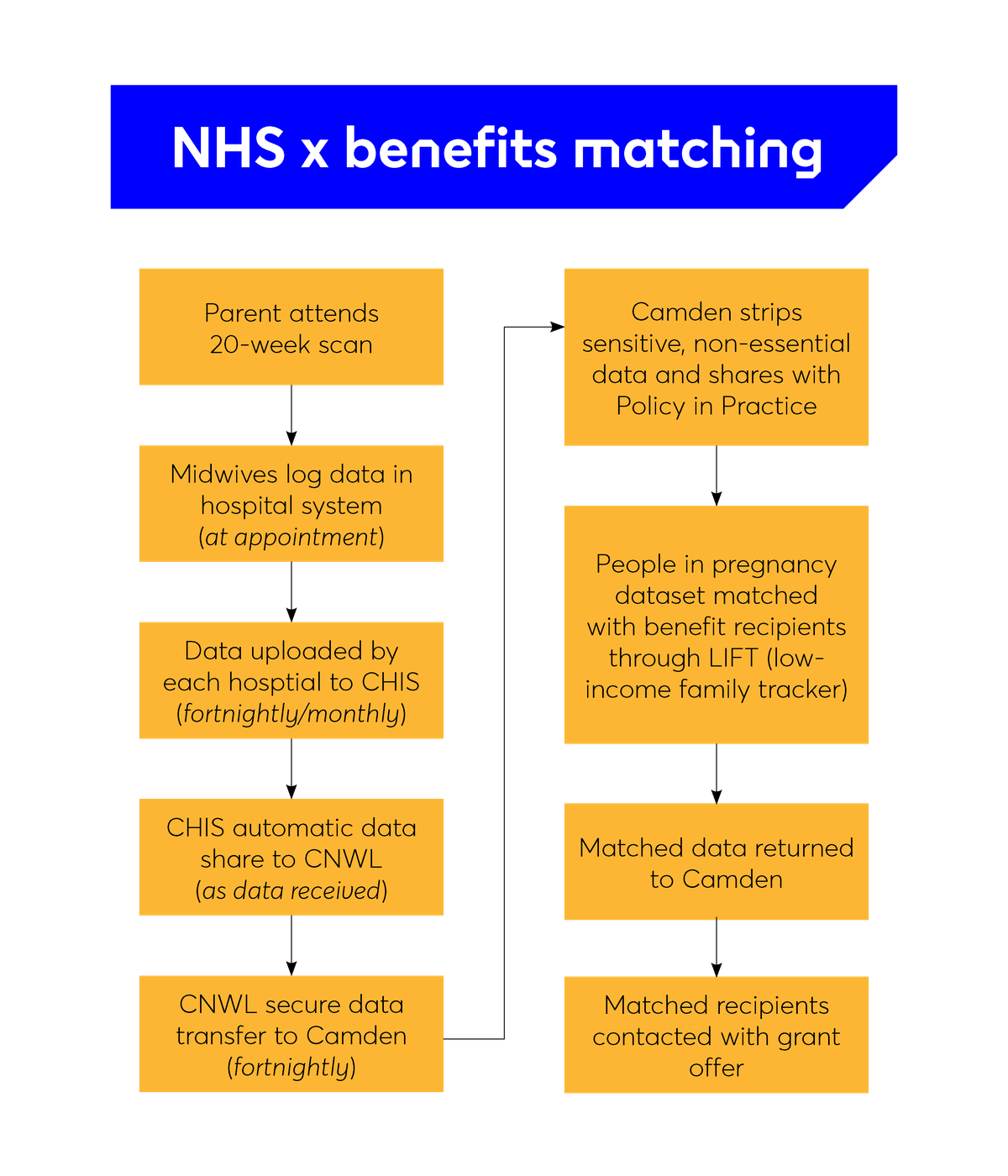

Our ability to provide proactive, targeted support in this pilot is underpinned by data flows. The data flows, data sharing governance and matching all take place behind the scenes from the perspective of the parents involved, meaning that they do not need to apply for the grant. For many, the first time they hear about the programme is when they receive the grant. To do this, we combine antenatal healthcare data (identifying pregnant people) with local benefits data (identifying low-income households). If an individual appears in both datasets, they will be offered the grant.

How to think about dataflows

Why it matters

Why are data flows important?

To follow one of our key design principles of reducing barriers to access, we knew it would be important to be able to reach out to people proactively, rather than rely on applications only. We know that it’s often the most disadvantaged groups who are least likely to reach out to or trust the council. If we wanted to be able to comprehensively deliver our intervention to all (or as close to all as possible) low-income families during pregnancy, we’d have to rely on our data to do this. While we recognise this data itself has gaps, and there would perhaps be those who wouldn’t be in receipt of benefits precisely due to this lack of trust, we still felt using this approach and creating an easy-to-access, non-coercive offer would be the best option to reach a higher number of people in a way that might lead to increased trust.

This meant we had to understand how data flowed through the different parts of the NHS, and where it was already being shared with the council, so we could expand on those existing processes and agreements. It was also important to know what data we would or wouldn’t be able to get (for example, would we get data very early in pregnancy from booking appointments, or later on from 20-week scans?). It was important to find this out early, so this could inform the design of the other elements of the programme, and so that we could ensure we weren’t creating something that would be impossible to deliver.

Why match data?

Matching NHS pregnancies data with benefit recipients data is the most comprehensive way Camden council has of identifying low-income families. Benefits are all means-tested, so by using the data we already own, we were able to avoid asking people to go through yet another process of application and means testing. However, we know this proxy of benefits data isn’t complete and that lots of people are underclaiming benefits they are entitled to. So, we also built in a process for self-referral (more details below).

Key consideration in Camden

Finding out what data exists and how to access it

Camden works in partnership with the NHS health visiting provider on its Integrated Early Years Service. We used this as a starting point to understand what data the NHS team we worked with had access to, and how we might extend this access to the team delivering the grant. We found that, by building on an existing data access agreement, we were able to get off the ground quickly with all our data centralised. In this case, it allowed us to access information from 20-week pregnancy scans across all hospitals that cover Camden through a single process. However, this data is coming from further downstream within the NHS itself, which means we are receiving it later in pregnancy (around 26-28 weeks) than if we’d approached each individual maternity ward and attempted to create new agreements with each (which would mean we’d get data at 22-24 weeks).

Navigating data protection and establishing the lawful basis for using data in this way

There are a number of principles under which the project team could establish an agreement to share data for the purposes of delivering an intervention such as this.

Camden already had an existing data agreement with the NHS for the purposes of delivering our health visiting service. We expanded this agreement under principles of substantial public interest but also of our duty under the Equality Act, of delivering services fairly and equitably across different demographic groups.

To expand on this agreement at Camden, we used the basis of Articles 6, 9 and 10 of the UK GDPR, and section 8 of the Data Protection Act 2018, which set out the acceptable conditions for processing and sharing personal and special category data for the purposes of an intervention like this. This work is also covered by our duty under the Localism Act 2011 (General Wellbeing), Care Act 2014, Children Act 2004, and Equality Act 2010. It was also under these principles that we were able to establish that our project would not need to operate under direct opt-in consent, but rather on an opt-out basis (meaning we would not need to wait for people to apply and directly consent to be contacted but we could contact them directly and let them tell us if they did not want us to reach out to them again instead).

As we were using benefits data as well, we also need to ensure compliance with the Department for Work and Pension’s Memorandum of Understanding, which governs the way local authorities use benefits data, and we framed this under the purposes set out in Annex C of this Memorandum, which detail how data might be used for local welfare provision.

Because we know that setting up data sharing and governance can take time, we started working on the data sharing agreement and the Data Protection Impact Assessment before we had a fully shaped intervention. As set out in the roadmap, we felt it was important to first establish that data sharing was possible in principle before dedicating months of work to designing a programme based on data sharing.

Identifying gaps in the data and how to account for them

We were aware in Camden that there would always be gaps in the data we hold. In our case, we identified two instances that were likely to represent our biggest gaps in data: people who were not being identified as pregnant in the NHS data (this could be for a number of reasons, including moving into the borough later in pregnancy, or receiving their maternity care at a hospital outside the borough); and people who were not in receipt of local benefits even though they would be eligible. We also knew there would be a percentage of Universal Credit recipients whose data we would not be able to access. There would also be some expectant parents under the age of 18 not entitled to benefits.

To mitigate against these risks, we also created a secondary route into our intervention, through a self-application form (see the application form for self-referrals). We circulated information through our Family Hubs, family workers, midwives and other community partners to pass on to families.

If someone believes they’ve been left out of our matching, they can apply through this form. When we receive an application, we assess each individually, as well as supporting relevant applicants with a benefit advice session to help them claim benefits they might be eligible for. This serves the dual purpose of supporting benefit uptake at the same time as accessing the pregnancy grant.

FAQs

FAQs

Which department does the pilot fall under within the local authority?

This is a collaborative project led by Camden Council, developed over a nine-month period in close partnership with internal teams and external organisations.

Internal Camden teams:

- Money Advice Camden (MAC) – funding the pilot and providing operational and analytical support

- Strategy Policy and Design (SPD) – service design and project management

- Public Health: Raise Camden – strategic leadership and mission alignment

- Early Years and Children’s Centres and Family Hubs teams – delivering support on the ground

External partners:

- Central North West London (CNWL) Maternity and Health Visiting teams – supporting connection with antenatal data

- Nesta – providing pro bono support on behavioural science, design and evaluation

- UCL and the Institute of Health Equity – contributing to ethical oversight and research expertise

What if I have no budget?

A cash grant may be out of reach without a dedicated budget. However, consider whether you can make the case for even a modest grant. It may be that this is an eligible use of the Department for Work and Pensions’ new Crisis and Resilience Fund, due to launch in April 2026. If effective, interventions to provide additional income to families with children and get families engaged with integrated services may well pay for themselves in terms of reduced fiscal costs in future.

Other elements of the programme could be implemented within existing budgets. For instance, linking data you already have access to, and allocating a portion of existing frontline staff’s time to work as Family Navigators.

What if I don’t have access to pregnancy data, but I want to do something?

Providing a proactive cash grant during pregnancy requires data on who is pregnant (from the NHS), matched with benefits data from the council. Pregnancy is a key period, and providing support during this time, instead of only after birth, is likely to be particularly beneficial for the baby. This is because of epigenetic effects as well as the fact that parents are not yet eligible for Child Benefit or the child element of Universal Credit.

However, the newborn period is also a time of very rapid brain development, during which maternal stress and nutrition can have important impacts on a baby’s development. We know from ‘baby bonus’ programmes in other countries, which are cash transfers paid shortly after birth, that these can improve health and education outcomes for children in low-income families. So, while there’s no evidence yet indicating the relative importance of additional income in these periods, the evidence that does exist suggests that providing the grant to families with newborn babies could be similarly effective as a grant given in pregnancy.

Providing a grant and other support in the newborn period would also be practically easier because councils would be able to use birth registration data they already hold, linked with benefits data, to target a grant or other support to low-income families with newborn babies. Therefore, if NHS data linkage is not an option, linking birth registration with benefits data could be a good alternative that does not require data not already held by the council.

How did you match the data?

In Camden, we worked with Policy in Practice to carry out probabilistic data matching using a combination of the parents’ full name, date of birth and address. This allowed us to match NHS maternity data with council-held benefits data while maintaining privacy and meeting data protection requirements. A Data Protection Impact Assessment and robust data-sharing agreements were key parts of this process.

What are the biggest data access challenges in a nutshell?

Accessing NHS maternity data is likely to be the most time-consuming part of setting up a programme like this. Health data is highly sensitive, so information governance and legal teams need full confidence in how it will be handled. Each partner may understand their own system well, but few will have oversight of the full end-to-end data flow, which can lead to delays, misunderstandings, or duplicated effort.

Start early by requesting a list of data fields or dummy data to understand exactly what information is available, how it’s structured, how often it is sent and when. This will help you scope which data fields are essential, propose a clear and minimal data request, and engage information governance teams with confidence.

Consider how data will be shared. If data is shared manually (for example, via secure email), even a one- to two-week delay can have significant knock-on effects on outreach, matching and delivery timelines.

It’s also worth noting that the NHS and Department for Work and Pensions’ datasets are not always fully accurate or up to date. You’ll likely need sophisticated matching logic to pick up eligible parents despite inconsistencies in names, addresses, or postcodes across datasets – especially to avoid missing people due to small errors or format differences in names and addresses.

Where possible, avoid building entirely new data pathways. Instead, build on existing data flows – for example, those used for health visiting or birth registration and explore how these can be linked or extended within your council’s existing infrastructure.

Finally, no data solution will ever be perfect. You may need to provide a self-referral route for families who aren’t picked up through data matching and work with community partners to identify eligible parents who may otherwise fall through the cracks.

What’s the simplest form of this I could create in my local authority?

If you're looking to get started quickly or with minimal infrastructure, one option is to pilot a small-scale, application-based model. You could invite pregnant people receiving benefits to apply, promote the offer through health visitors or Family Hubs, and provide a modest cash grant alongside a warm invitation to your Family Hub. This approach avoids the need for complex data sharing and allows you to test demand and outcomes in a manageable way.

What if I don’t work for a local authority?

You can still play a role. If you're based in the NHS, voluntary sector, or a university, you might partner with a local authority to support a pilot, offer maternity data under a governed agreement, or help evaluate the impact. Local authorities may also welcome your support in co-designing outreach or delivery models, especially if you work closely with families who would benefit from the grant.

What are the biggest safeguarding concerns to be aware of?

The main safeguarding risk is inadvertently disclosing sensitive information, such as someone’s pregnancy or benefit status, to others in the household. Communications, whether by letter, text, or email, should be carefully worded to avoid putting anyone at risk, especially in cases of domestic abuse or coercive control.

It’s also important that families feel in control. Participation should always be optional, and messages should make it clear that there are no conditions attached. If someone discloses safeguarding issues (such as abuse or mental health issues), staff should be prepared to respond sensitively and know how to refer or escalate to appropriate support.

In some cases – such as where someone has a history of addiction, financial coercion, or substance misuse – it may be appropriate to offer alternative forms of payment (for example, gift cards, staggered payments) in consultation with the individual and relevant professionals. This should be done carefully and only where it supports the person’s safety and wellbeing.

Above all, a trauma-informed and respectful approach helps ensure the grant offer feels safe, empowering and genuinely supportive.

Are you worried that parents will spend the money unwisely?

This concern is common but not well-evidenced. Research shows that when families in financial hardship receive unconditional cash, they typically spend it on essentials such as food, bills and baby items. Many low-income parents already budget carefully, and the stress of poverty often makes it harder to plan or engage with services. By reducing financial pressure, even temporarily, the grant can create space for parents to focus on their wellbeing and their baby.

In our pilot, we took a trust-based approach: the grant is unconditional and not monitored. Where appropriate, we offered gentle guidance or signposted financial support and Family Hub services, but never placed restrictions on spending. Our early feedback suggests that this approach felt empowering, respectful and helped build trust with services.

What approach should I take to supporting people with no recourse to public funds?

Families with no recourse to public funds are often excluded from financial support, yet they may face some of the most significant challenges. If your funding allows, it’s worth considering whether you can include these families – either by using discretionary funds or by working with partners who can help identify and support them. Community organisations can also play a key role in making sure your programme is inclusive, safe and accessible for those who may be hesitant to engage with official services.

What will Camden do if the pilot shows positive outcomes?

If the evaluation suggests that the grant has positive outcomes, we’ll explore options for scaling or sustaining the approach. This could include, but is not limited to:

- making the case for local or national policy change

- sharing learning with other boroughs

- integrating the approach into existing services (such as via health visiting pathways or wider poverty prevention programmes)

- seeking external partners or philanthropy to expand reach.

We’re also interested in further testing the model, including adaptations (for example, for families with newborns or other target groups, different grant values), and strengthening the evidence base through pooled data and cross-borough collaboration.

Next steps

Next steps

If you work in a local authority and are considering ways to provide earlier, more joined-up support to families, the Camden Council and Nesta teams would love to hear from you.

To stay in touch with what both teams are working on, you can:

- email [email protected] to get more info about this project

- sign up to Nesta’s mailing list and be sure to tick the box for ‘A fairer start’ newsletters

- sign up to Raise Camden’s newsletters by contacting [email protected].

Toolkit assets

Toolkit assets

Communication and outreach assets

- Offer letters

- Email template

- Text message examples

- Navigator conversation guide

- Navigator communications (for example, closing email after a case)

Parent-facing and eligibility materials

- Application form for self-referrals

- Contact details and payment selection form

- One-page info sheet for midwives and partners

- FAQs for midwives and partners

Process and data flow assets

Evaluation and outcomes

Foundations and planning tools